Haiti with no tourists, 2004

Pool at the Hotel Oloffson, Port-au-Prince

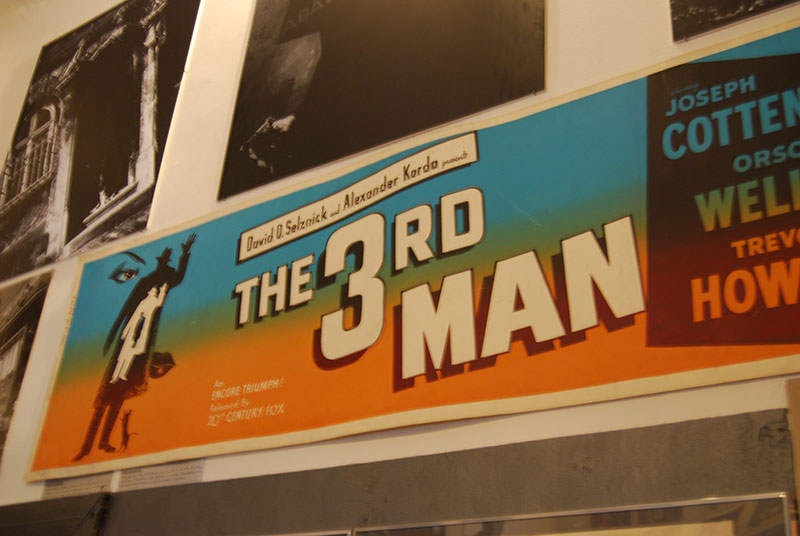

IN The Comedians, Graham Greene’s novel about the dark days of Haiti’s Tontons Macoute and Papa Doc, his narrator, Mr Brown, invites a friend to dinner at his hotel to meet Mr and Mrs Smith, evangelical vegetarians from the United States: “Come to dinner on Saturday… and meet the only tourists here.”

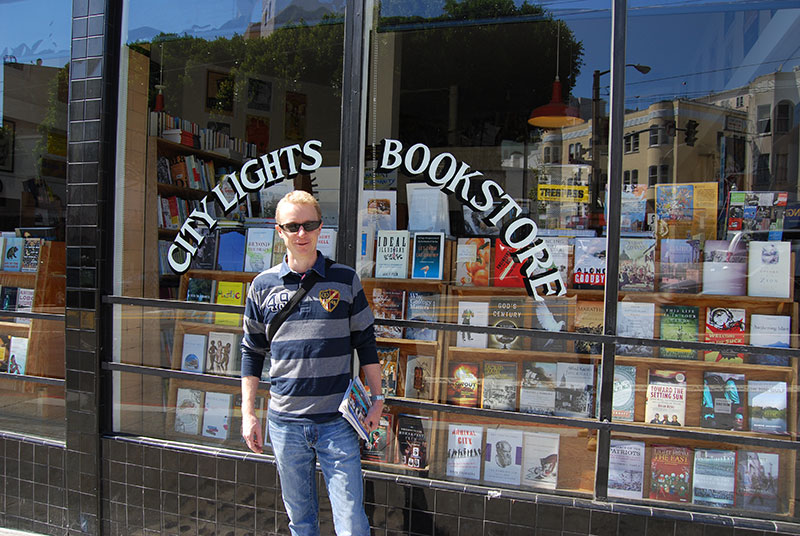

Last week in Port-au-Prince, myself and the photographer Doug McKinlay, staying at Hotel Oloffson, on which Greene based the Hotel Trianon in his 1965 bestseller, were by all accounts in the same, quite surreal, position as the Smiths. We may not have been evangelical vegetarians – the fried chicken, the steaks and lambi a la creole (conch in spicy creole sauce) were just too good to be preaching against meat-eating – but we were almost certainly the only tourists there… as almost everyone we met told us.

“You’re tourists!” exclaimed a Canadian documentary film-maker researching a series on voodoo, who joined us on the Oloffson’s gingerbread verandah on our first night, clutching a rum punch a la Joseph, Mr Browns’ limping barman (his limp post-dating a visit from the Macoute). “Hey, these guys are tourists!” he called out to his camera crew, who stared at us as though we were circus show freaks. “We never thought we’d see any tourists!”

It felt, as you might expect, extremely odd; especially with news from Gonaives coming in thick and fast. News agencies on the free internet terminal at the Oloffson reported mass burials and food riots, with “survivors drinking and cooking with water from ditches containing rotting bodies and raw sewage”. And there we were with our rum punches, lambi and bottles of Prestige beer – guiltily building up a tab. The ceiling fans whirred, the cicadas screeched and the sun set in a blaze of orange through the tropical creepers and trees down the hill towards the Presidential Palace.

The latter was – in a further twist – currently occupied by United Nation troops and members of an interim government put in place after President Jean-Bertrand Aristide was forced into exile in a popular revolt in February this year. Aristide, currently in South Africa, had introduced his own Macoute-style secret police, the Chimeras, after being democratically elected in 2001. “There are 10,000 of them still out there with guns,” said one local insider we met on the Oloffson’s veranda – 40 years after Greene, still the place to find out what’s going on in Haiti.

Floods or no floods, these were not exactly tourist-friendly days in Haiti (and it hadn’t exactly had many of them in the first place). The “lost world” of “naked girls in the pool” in the 1940s and early 1950s, so lamented by Mr Brown, was well and truly lost, with few who could even remember it.

But before travelling, I’d contacted a local travel agency and spoken to Jacqui La Brom, one of the only English-language guides in the country, a Bristolian who originally came to Haiti as a missionary in the 1970s, and she had convinced me that conditions had settled since the February coup: “It’s fine. People are eating out at restaurants again in the evening. If you sick to the mainstream sights, steer clear of the slums, and don’t go out at night alone, it’ll be fine. Stuff the Foreign Office advice (which was against ‘non-essential travel’), they always overdo it – I’m always writing to tell them so.”

Jacqui met us at the bus station, after we’d crossed the border after a six-hour drive from Santo Domingo, the capital of the Dominican Republic. “Oh it was going to be a wonderful year,” she sighed. “Everything was starting to go so well. It was the 200th anniversary (Haiti celebrated its bicentenery on January 1) and we had all these bookings lined up. Beautiful, it was all going beautifully – then: boom! And now there’s Goinaves. Oh, it’s dreadful!”

Jacqui, who reminded me of a purposeful-but-slightly-eccentric leading character in an Anne Tyler novel (she plays bridge every Tuesday evening, is a former president of the International Women’s Association, and her favourite pink T-shirt bears the logo “Supergirl”), kept on talking… and talking. She surely, Doug and I agreed after a couple of days, merits some kind of international medal for oratory skills, if not just for long breathes.

“There’ll be 6,000 or so troops out here by the end of the year. But they’re not doing anything. They’ve spent a fortune on vehicles – which is very nice for all the rich people here who sell Nissans. But you don’t often see them on the streets. They’re supposed to be keeping the peace, but people have been shot in front of them and they’ve done nothing. (She hadn’t mentioned this when telling me about the travel conditions).”

As she says this, a white UN four-wheel drive passes by. “See, that’s just from the headquarters round the corner – whenever they do roadblocks, it’s always close to the headquarters, so they can get back easily.”

On the floods: “There’s a big problem across the country of people building on land in ravines. They can’t afford anywhere else. They are so poor. But nobody’s going to chuck them out of a riverbed.”

So what does a tourist – the only tourists – do in Haiti? And does this change when there are devastasting floods (which were localised and had not affected other parts of the country) and continuing political rumblings (Aristide supporters began demonstrating, literally the day after we departed – forcing the UN into more visible action in Port-au-Prince)? I’d been attracted by the Oloffson, with its ghosts of The Comedians; the mystique created by voodoo, which is said to be practiced by as much as 90 per cent of the population; the country’s remarkable and troubled history; and by the sheer curiosity of visiting such a little-visited place.

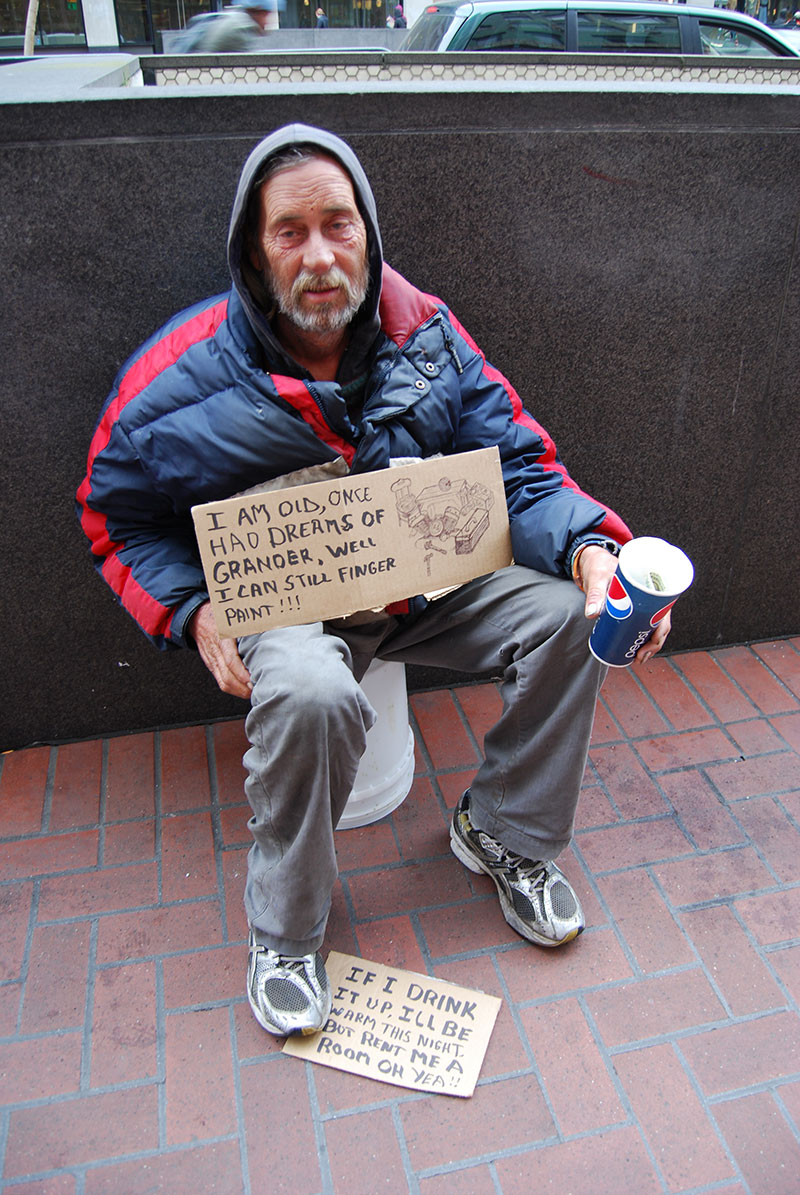

We began with the history, via a brief lecture. “There are nine words I don’t want you to mention,” said Jacqui, in the Place des Heros de l’Independence, opposite the bright White House-style National Palace. What, Jacqui, we asked. “That ‘Haiti is the poorest nation in the western hemisphere’.” A nice try, and based on her belief that “Haiti gets a bad press”. But some stark stats prove the point: gross national income per capita US$440; life expectancy for men of 49 years and women of 50 years (people in the neighbouring Dom Rep can expect to live 15-20 years longer); half the nation’s wealth owned by French-speaking mulattos, who make up just one per cent of the population, while the Creole-speaking black majority is impoverished; tiny percentages of the land left with forests (deforestation being one of the main blames for the strength of the effect of Hurricane Jeanne).

As several small boys offer to polish my sandals – “Eh blanc!”, looking at my feet, “Eh blanc!” – we saw the statues commemorating the heroes of Haiti’s battle for independence. Toussaint Louverture, who in 1801 declared himself Governor for Life on the island, but was subsequently tricked by Napoleon and jailed in France – his chin jutting defiantly. Jean-Jacques Dessalines, who declared independence on January 1, 1804. Henri Christophe, who helped lead resistence in the north.

This should be a year of great celebration in Haiti – a year of rejoicing for the world’s first black-led republic, the first freed-slave nation. Instead “things haven’t worked out quite like that,” said Jacqui. A dreary, half-built memorial – not open to the public yet, and no one knows when it will – looks more like a practice tower for firemen. Yet Haiti freed its slaves 29 years before the British, and 60 years before the US Civil War.

Doug and I tracked down Issa El Saieh, the Haitian-Syrian who Graham Greene turned into Hamit, the Syrian storeman who provides a room for Mr Brown’s adulterous affair in The Comedians – the name of the book came partly from the “comedy” of the private lives of the charcters who lived during Papa Doc.

It wasn’t difficult. The 85-year-old runs an art gallery on Rue Chile, a few streets from the Oloffson, in a big echoing white mansion with a sweeping view across the capital – past the palace and the cathedral to the slums near the port, where rubbish was burning. We were his only visitors. What did he think about what’s been going on? “Terrible, just terrible: if I was a tourist, I wouldn’t bother coming here. I haven’t sold anything for months, not that I really give a damn.”

In better times, Issa sold Greene a Philippe Auguste for about 50 dollars – a “crazy sum” (as in crazily low on today’s likely valuation) – and became friends: “He was a nice guy, but he could also be a pain in a way. If he didn’t like you, you’d better watch out. He’d bad mouth people.”

Had he any news of Aubelin Jolicoeur, on whom Greene based the character, Petit Pierre, a gadfly gossip-columnist with Papa Doc connections, once known to prop up the bar – and never pay for his rum punches – at the Oloffson. “No, but I bet he’s still not paying for his drinks. He used to run around Port-au-Prince like he ran the country. I’ve known him since we were in our teens.”

Issa’s art is stunning, bright primary colours, – realism mixed with abstract works – but he would not mention prices. “I’ve got one foot in the grave and one on a banana peel,” he told Doug as he showed him one picture, “so I only want to sell if you’re really interested”. When we go, Issa, who has Greene’s quizzical eyes, cried after us: “Make sure you tell tourists to come and see me: I need somebody to lie to!”

Moro Baruk, who runs a small art gallery in his name in Jacmel, a sleepy seaside town with charming-but-dilapidated 19th century colonial houses, where we make a pit-stop before traveling north, was also selling badly. How many tourists had he had this year? “Well, that depends on how you define tourist,” he replied playfully. We agreed that it did not count aid workers taking breaks. “Four,” he said. “Yes, four.”

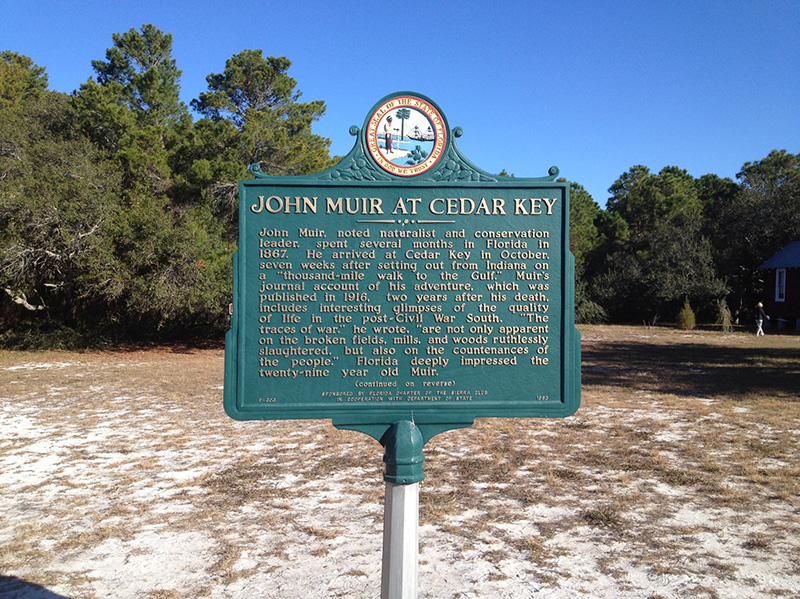

Haiti’s history comes alive in the north, a few miles from Cap-Haitien – at probably the world’s least visited major attraction: the Citadel. Built by Henri Christophe from 1805-1816, it is a monument to the slave revolution and as breathtaking as the pyramids (go if you don’t believe me). It is the world’s biggest fort, with walls 30ft wide designed to keep out the French – who were expected to come back for a fight (but didn’t).

It is just 60 miles from Gonaives, but was unaffected by Hurricane Jeanne, as was the surrounding area. We are taken to the top by Maurice Etienne, himself the descendent of a slave ship from Benin that made the mistake of calling at Cap-Haitien while Christophe was in charge: he freed it and imprisoned the captain.

“When this was built, everywhere in the Caribbean had slavery. And in North America, South America: nothing but slavery,” said Etienne, who had a bushy black beard and who said he works for three months each year as a taxi driver in New York City (he is divorced from an Amercan woman) to make ends meet. “Christophe said ‘listen guys, build this and be free forever’. They said ‘ok let’s go for it’. You see dying for this building was like being sent straight back to Africa, to the motherland, to freedom. (About 5,000 people did die). And when it was finished it was thought it would be the saviour of the nation.”

We talked about what had happened this year – the politics and the floods. “I feel like dying, really I do. After 200 years we have been reduced to this, reduced to having the UN here. We can’t look after ourselves. It feels like we have been invaded. Invaded by the UN, which everyone just thinks of as the USA. I don’t see what we’re going to do from now – if the truth be told.”

It was a strange, and often moving, experience, being the only tourists in Haiti.