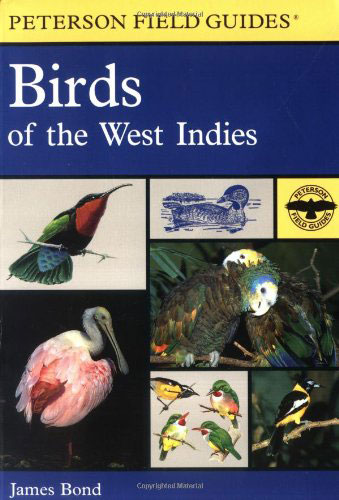

Cute, cuddly in Peru… and it comes with chips

View at Machu Pichu (more pictures at the end of the article)

THE guinea-pig stared at me. I stared at the guinea-pig. Then I took a deep breath, counted to three — and ate it.

There’s much more to visiting Peru than taking in Machu Picchu, the 500-year-old “lost city” of the Incas, which is considered the must-see attraction of South America — and eating guinea-pig, a local delicacy, is one of the more memorable diversions.

It tasted awful, although it looked, on first inspection, rather natty. With great aplomb, brandishing trays on shoulders, a team of waiters had brought forth our roasted creatures (with side orders of chips). Each guinea-pig, front legs perched on a sweet potato, wore a half-tomato “cap” with a decorative mint sprig. The animals’ mouths were propped open by slices of carrot in what disconcertingly seemed like hey-how-you-doing smiles.

How to eat it? Our guide advised hands: “It tastes better that way.” We tentatively pulled at haunches. Jon, sitting opposite, was having a minor fit. “I don’t want to think it’s a blinkin’ rat,” he muttered. Natasha, our only non-eater, had already stomped off, with a parting: “All of you, you’re all monsters!”

It was hard to disagree. The meat had a metallic, fizz-on-the-tongue aftertaste. And despite my best efforts, I couldn’t help imagining the cuddly things scurrying across the floor of a village hut, as we had seen them just a day before, on a visit to Ollantaytambo.

Visiting Peru consisted of a sequence of indelible memories, the highlight of which was undoubtedly Machu Picchu. But tour operators are increasingly aware that the breathtaking sight has become a victim of its own success: on some days more than 3,500 people scamper over its ancient terraces. Which is why many, including Cox & Kings, the company I travelled with, are now highlighting visits to other parts of Peru, and other experiences (small-animal eating being just one of many), along with trips to the famous Inca ruins.

We were staying for four nights at the Libertador, a four-star hotel in Cuzco — just around the corner from the pretty Plaza de Armas with its fountain, church and cathedral. The latter includes a giant 18th-century painting of the Last Supper, which featur- es, as its centrepiece, a rather scrawny-looking guinea-pig.

The idea of our week-long whistle-stop trip was to see as much of the region as possible, including sights that many tourists fail to visit because they are so obsessed with the Big Attraction. We were leaving the now-well-and-truly-found city till the final day — planning to visit in style on the Orient-Express train Hiram Bingham, named after the American who was the first outsider to come across Machu Picchu in 1911. It turned out to be a great way of dividing our time.

“We will try to avoid the crowded places,” said Carlos, our guide. “First, we see Sexy Woman!” He was referring to Sacsayhuaman, which is pronounced just like “sexy woman” — and is presumably “Gag Number One” in the “Get Them Laughing” Cuzco tourist studies exam.

Sacsayhuaman is a fort overlooking Cuzco. It was built in the 15th century and it was here that the Incas launched a counter-attack against the Spanish conquistadors, who were led by the ruthless Francisco Pizarro, in 1536. Pizarro’s men, who had arrived in Cuzco four years earlier, won the day. “It was bloody — the Incas’ last stand. After this it was all over for them,” said Carlos.

Outside the walls, three children, aged about 8, dressed in traditional multicoloured outfits, were offering themselves for pictures — one had a green parrot on his head, another held a rope attached to a fluffy white llama, “Please mister, take picture. One sol,” they said. One sol is about 20p.

Poverty is rife, despite the tourist boom. Street urchins prowl Cuzco at night, hanging on to people’s clothes and demanding soles in exchange for grubby packets of gum. Muggers and pick-pockets are, however, rare — a decade ago they were common. Better policing and a realisation that tourism is the region’s “golden goose” have been key, said Peter Frost, author of Exploring Cuzco, the best guidebook, who I met in the hotel bar one evening.

Some locals blame hardships on Peru’s colonial past. One of our guides in Lima — who had shown us the ruins of Caral, recently discovered 182km (110m) north of the capital and considered the oldest in the New World — surprised us by saying: “If only we’d had the British, not the Spanish. The real problem with us is we had the wrong colonialists!”

After seeing other battlements above Cuzco, we drove to the salt pans of Maras. They are spectacular. Since Inca times, farmers have operated evaporation pans, taking advantage of an underground salt supply; proof that this part of the Andes was once beneath the ocean. There are about 3,000 pans, each about 5ft by 10ft and coloured a shade of cream, white or ochre-brown, depending on the stage of processing. Together they look like a huge, lopsided artist’s easel.

Near by is Moray, another astonishing Inca sight. Three enormous circular terraces are built into the landscape, where the Incas used to encourage crops to grow at different levels (where there are markedly different temperatures) so they could adapt to varying altitudes. Amazing evidence of ancient science; although many “New Age” tourists claim it’s a UFO site.

We saw Ollantaytambo, another fort, believed to be shaped like a giant llama. No one is sure if this is true, partly because it has been damaged and partly because the Incas left no written records. “Inca theories are 60 per cent incorrect, 30 per cent have a chance of being true, and only 10 per cent are correct,” said Carlos, a 10 per cent man.

And so to Machu Picchu, 90 miles northwest — the most remarkable place I have visited, and I include the pyramids in Egypt and Petra in Jordan. The crowds were thin — we had arrived at 2pm on the Hiram Bingham when most people were having lunch.

The views and setting were mind-blowing, everything we had imagined and more. We snapped away and soaked up the scenery — thankful that this had been left to the end of the trip as anything afterwards would have been an anti- climax. We also agreed that while Machu Picchu is not the be-all-and-end-all of Peru, it clearly must, as Unesco hopes, be protected.

Unesco, we learnt, wants a 2,500-tourists-a-day limit, and a plan of this sort looks set to be put in place soon, along with a ticket price rise from the current £15. Authorities put a similar restriction on the numbers using the Inca Trail trek to Machu Picchu in 2001; now only 500 a day can go, porters included, and it must be booked 45 days in advance.

On a terrace looking across the mesmeric valley, I met Yashpal, a “naturopathetic physician, mystic minister and ambassador of the peoples’ world” (so said the card he handed me), from Port Townsend, Washington, in the US. “Wow! These peaks round here, man . . .” he said dreamily, wearing a white floppy hat, but no shoes, so he could be “more connected to the earth”.

“These peaks, man. You can just imagine this as a temple of nature, why they wanted to be here. Man, they just must have worked with nature . . . to have been totally at one with nature, man.”

Maybe, man, I thought. But not with the guinea-pigs. They would have eaten those.

Need to know

Getting there: Tom Chesshyre travelled to Peru with Cox & Kings (020-7873 5000, www.coxandkings.co.uk) which offers a similar luxury, tailor-made eight-day tour from £2,360pp. A nine-day Highlights of Peru group tour, including a night at Machu Picchu, costs from £1,395pp.

Red tape: No visa required.

When to go: Best weather is from February to October. Guinea-pig: Kusikuy on Calle Suecia in Cuzco is the most traditional guinea-pig restaurant; ask your concierge to book it.

Reading: Exploring Cusco by Peter Frost (Nuevas Imágenes, £7.50); Peru (Rough Guides, £12.99). Notebooks of Don Rigoberto, by Mario Vargas Llosa (Faber, £7.99).

Further information: Latin American Travel Association (www.lata.org); Perurail (www.perurail.com). Altitude sickness: To minimise risk, spend as long as possible acclimatising to places higher than 2,500m (8,200ft), such as Cuzco, before doing any strenuous exercise.

First published in The Times, January 28 2006

Traffic jam near Lima

Spot the llama in Cuzco

On the edge of Cuzco

Maras salt pans

Guinea-pigs at local home

The Hiram Bingham train

The Hiram Bingham

View from the train

View from the train

Machu Picchu

Llama at Machu Picchu

Machu Picchu

More llamas at Machu Picchu

Unexplained arrival of riot police in Cuzco

Eating guinea-pig