Here’s a selection of my “weekend break” contributions in the UK… from Dudley to Falkirk, via the Pennines and the Cotswolds:

A weekend in… Tetbury, Gloucestershire

At the Top Banana Antiques Mall, in the market town of Tetbury, it felt as though we’d entered an Aladdin’s Cave. Porcelain from the 19th century lined shelves next to cabinets stacked with delicate figurines and vintage jewellery. Barrels made of varnished wood and shiny brass stood next to tables crammed with buffed candlesticks. Fish-eye mirrors, English country landscapes and old prints cluttered the walls.

Everywhere you looked there was a curiosity: carved lion-shaped bookends, miniatures of lords and ladies, Art Deco lamps. In a hallway I came across a print of Fleet Street dating from 1800, which showed an old archway (that no longer exists) and tiny figures walking past the Inns of Court. After a bit of haggling with a whiskery attendant — and handing over £30 — it was mine.

Tetbury has to be one of the best spots in the country for antique-hunting. As we walked down Long Street, on a family outing, we stumbled on shop after shop filled with wonderful bits and bobs. My parents picked up a Victorian chalkboard, my sister a 1930s brass doorbell, and my brother an old book entitled The King’s England: Gloucestershire by Arthur Mee, which dated from 1938.

After browsing in a shop filled with prints of ancient pugilists and old racing scenes, we stopped at The Snooty Fox inn by the Market House. The latter, built in 1655, holds pride of place in the town, with three mustard-yellow floors supported by a maze of stone pillars. At the top is a bell-tower with a copper cupola. Down amid the pillars, a stall was selling fresh vegetables. Mee’s verdict was that Market House could not have changed “since Waterloo”, while Tetbury was a “quaint … old-fashioned little place high on the Wiltshire border near the source of the Avon”.

It still is. In The Snooty Fox’s cosy bar we tucked into sausages and mash by a blazing fire, watched over by George, the inn’s resident Great Dane. Sausages came in a variety of types — the pork with smoked bacon and cheese, and the honey and mustard ones went down best. So did the real ale, amid the wooden tables filled with chattering folk (many with bags of antiques). Soft light filtered through mullioned windows. What a great place to while away an hour or so.

Highgrove House, home to the Prince of Wales and the Duchess of Cornwall, is south of Tetbury, and there’s a shop (highgroveshop.com) close to the Market House. It’s not cheap. Jars of lemon curd and pots of mustard are £6, while a pair of purple wool socks was an eye-watering £27.50: Britain’s poshest socks, we wondered? The gardens at Highgrove are open to visitors until mid-October; tickets must be booked in advance. But you do not have to book for Westonbirt Arboretum, just down the road. After taking in the late 18th-century Gothic splendour of Tetbury’s Church of St Mary the Virgin — with its towering spire — we went for a stroll along paths snaking between the aboretum’s 18,000 trees, with 2,500 species from around the world.

There are 17 miles to walk and signs inform you of the exotic heritage of each species: Brazilian pines, Saharan cypresses, Canary Island junipers. Westonbirt is a wonderful setting, with surprises around every corner. Planting of the arboretum began in 1839 under the supervision of Robert Holford. He left a fine legacy. It’s a good place to clear your head in the oxygenated air before heading back to the scrum of the antique shops — ready for a haggle in Gloucestershire’s little antiques HQ.

Need to know

Where to stay

The Snooty Fox (01666 502436, snooty-fox.co.uk) is in the heart of Tetbury with double rooms from £80 B&B and four-poster rooms with hot tubs from £210 B&B. The inn has good dinner/B&B prices: doubles from £120 and four-poster rooms from £250. The Hare and Hounds (01666 881000, cotswold-inns-hotels.co.uk) is a coaching inn with a modern makeover close to the entrance to Westonbirt. B&B doubles are from £115, superiors from £175, and the big gamekeeper’s cottage costs from £250.

Where to eat

Three courses in the formal restaurant at The Snooty Fox are from about £27. Bar meals of bangers and mash, haddock and chips, and tasty pies are £10. The Hare and Hounds also has a bar snack menu, and a fine dining restaurant with main courses including pan-fried beef with béarnaise sauce, rabbit, seabass and lemon sole. Three courses are available from £39.50.

Further information

Cotswolds.com, visittetbury.co.uk, highgrovegardens.com (tickets £22.50), www.forestry.gov.uk/westonbirt (tickets £5 until end of February, £8 until end of September, £9 during autumn).

First published in The Times, July 20 2013

Great British Weekend: the Vale of Durham

National Railway Museum, Shildon, County Durham

On first inspection, the National Railway Museum at Shildon in County Durham — known as “Locomotion” — did not exactly set the pulse racing. A gritty car park with a handful of vehicles sloped towards the main building: a dull-looking warehouse. Rain spat down. We drew to a halt and ventured forth across a grim yard … and were in for a revelation.

Inside, we found ourselves in a stunning space packed to the rafters with dazzlingly shiny old trains. Teak carriages polished to perfection (some containing plush royal compartments in which Edward VII and Queen Alexandra rode) were lined along corridors with 1970s InterCity locomotives here, and protoype “tilting trains” there. Olive-green steam trains from the 1890s led to beautiful sky-blue 1950s expresses with Art Deco lines.

It was a veritable trainspotters’ heaven. Indeed, there were a fair few trainspotters about, pointing cameras, making notes and carrying rucksacks with flasks poking out. “We do get a lot,” admitted George Muirhead, the museum manager. “They’re an important part of our business.”

Locomotion opened in Shildon in 2004, filling its vast hall with restored trains that could no longer find space in the crammed main National Railway Museum in York. The location was chosen because it was from here that the Stockton and Darlington Railway began in 1825 with the world’s first steam-hauled trains on a public track; the locomotives were built by the railway pioneers George Stephenson and Timothy Hackworth.

In a corner, near a display explaining the importance of trains in the popularisation of football (they allowed fans to get to matches), there was an example of one of the early carriages. It looked like a stagecoach, with a first-class cabin between two second-class seating spaces, made of curving wood and painted burgundy and gold.

Locomotion was only one of the highlights of what turned out to be an intriguing weekend’s journey across the Vale of Durham, the swath of land that surrounds the city of Durham.

We made our way to the nearby town of Bishop Auckland, home to Auckland Castle, the official residence of the Bishop of Durham. With its castellated roof, mottled stone walls and lawns, it looked splendid on its hill, surrounded by fine gardens and 800 acres of parkland. The castle is renowned for its striking masterpieces by Francisco de Zurbarán (1598–1664), which depict Jacob and his 12 sons, and which were purchased by the Bishop of Durham in 1756 “to lament the failure of lawmakers to grant freedom from oppression for the Jews in England”, according to a panel.

It was an interesting spot to while away an hour before heading north — unable to resist a stop in Durham to take a look at the Norman cathedral. We climbed to the top of the tower (66 metres) and looked out from a wooden deck across patchwork fields coloured emerald and yellow, with the muddy waters of the River Wear down below. It’s a wonderful view. Bill Bryson once quipped that Durham got his vote for “best cathedral on planet Earth”, and from the top you can understand why.

Next up was Beamish: the Living Museum of the North, about ten miles to the north, which we visited after catching a glimpse of the looming shape of Antony Gormley’s sculpture, Angel of the North, beside the A1. Like Locomotion, it was a terrific surprise, set in 300 acres of land — a kind of Disney of the north, industrialisation and all things flat-cap.

There were lovely old trams and buses taking visitors from a recreated pit village with a Methodist chapel to a mini-town complete with a 19th century Barclay & Co’s bank and a Sun Inn pub — which served pickled eggs for 50p and pints of Beamish Hall XB bitter for £2.90. We also visited and a section with a steam railway and a replica of Stephenson’s Locomotion No 1, built for the Stockton and Darlington Railway. Trains again! You can’t seem to get away from them in these parts.

Need to know

Where to stay Rockliffe Hall (01325 729999, rockliffehall.com) is a lively hotel in Hurworth-on-Tees, Co Durham. It’s got a fine-dining restaurant, a large spa with an indoor pool and various hot tubs, steam rooms and saunas. B&B doubles are from £190. Or try the Morritt (01833 627232, themorritt.co.uk) in Greta Bridge, near Barnard Castle, Co Durham, which has a more traditional style and B&B doubles from £90.

Where to eat Other than Rockliffe Hall, the café at the entrance to Beamish offers great sandwiches with chunky brown bread and slices of ham for about £4 each. The pickled eggs at Beamish’s Sun Inn are also recommended.

Further information Locomotion (01388 777999, nrm.org.uk), Shildon, Co Durham — admission free. Beamish (0191 370 4000, beamish.org.uk) is in Beamish, Co Durham — adult entry £17.50, children £10. Local information is available from: thisisdurham.com.

First published in The Times, May 26 2012

Great British Weekend: Glencoe, Argyll

On the slopes above, a cyclist wearing a fluorescent helmet was flipping from side to side, occasionally leaping upwards before jolting to earth and sliding his mountain bike round a corner. It seemed impossible he could negotiate so many rocky bumps and slip downwards so fast.

Then I turned to my bike, a red and white Kona with RockShox suspension, and tried to work out the gears. I hadn’t cycled for a couple of years. I skidded jerkily around the vast, almost empty, gently sloping car park at Glencoe Mountain Resort, almost catching my jeans in the chain and taking a tumble.

“It’s possibly the most dangerous downhill course in the country,” said Xander MacFarlane, who oversees bike rentals at Glencoe, one of Scotland’s best-known ski resorts, which switches over to mountain bikes this week after the ski season. “Even good people sometimes walk down the gnarliest bits. You’ve got to be really on the ball.”

Luckily, I was not about to try one of Britain’s most dangerous mountain bike rides. Instead, I was to take a gentle journey down the hill, along a crumbling old road and up a much more gentle gradient — a very peaceful way to spend half a day.

Over a little bridge, I came to a gate with a sign by the Scottish Rights of Way & Access Society announcing that this was a public path through Rannoch Moor to Loch Laidon. Under a pewter sky, I soon found myself pedalling through a deserted, rocky green world, along a gravelly path flanked with purple thistles, dandelions, buttercups and a narrow, tea-coloured river.

It was a great taste of mountain biking, with enough “up” to put the gears into play, and the strange landscape to keep you captivated. An hour or so onwards, past a couple of copses, I stopped and looked back at the dramatic pyramid-like shape of Buachaille Etive Mor (a famous climbing mountain) towards the ski slopes, which seemed many miles away — glorious Highlands scenery.

Back at the main resort, I reached the mountain top via the cable car, with a thin waterfall tumbling below and Ben Nevis in the distance. Then I walked down the rocky mountain path, avoiding the “DANGER BIKE” areas; about half an hour’s scramble.

Afterwards, I drove to Glencoe Village proper, about ten miles along the A82. This is a village with a population of about 500, a cute high street with a handful of cafés, an art gallery and a grocery shop. It’s also got a top-notch folk museum.

The museum tells the story of the Glencoe Massacre, which took place on February 13, 1692, when a garrison led by Captain Robert Campbell — containing many of the Campbell clan — massacred 38 of the local MacDonald clan, who had been hosting and entertaining the garrison for a fortnight. This action was taken on the grounds that the MacDonalds had not declared allegiance quickly enough to William, Prince of Orange. A further 40 women and children tragically died of exposure after homes were burnt down.

There are artefacts in the higgledy- piggledy museum dating from the period, including a chest said to be taken from the building in which the massacre took place. “We get people coming in saying: ‘I don’t like to admit it, but I’m a Campbell,’” said Rhona Paterson, one of the trustees. “And there are still a lot of MacDonalds who live in Glencoe.”

At the end of the high street I visited the slim stone memorial to those who died. Then I drove up a hill to Glencoe Lochan, a small loch in a tract of forest transplanted from Canada by Lord Strathcona in 1895 to make his Canadian wife of Native American descent feel less homesick; a strategy that apparently failed. But it’s a peaceful place for a walk, hidden away in the trees. There is no shortage of walks — and cycle rides (some more dangerous than others) — around Glencoe.

Need to know

Where to stay

The Kings House Hotel (01855 851259, kingy.com), Glencoe, Argyll is the closest hotel to the ski resort, with simple-but-cheap rooms and a bar. Doubles from £64.

Where to eat

The ski resort’s café serves simple but hearty fare such as baked potato with haggis (£4.60), rolls filled with sausage, egg or black pudding (£2.50), or scampi and chips (£6.60). A soup and a roll is £3.30.

Bike hire

Glencoe Mountain Resort (01855 851226, glencoemountain.com); mountain bikes are £25 for a day. Tough downhill bikes are £90, including body armour.

Further information

Visit Scotland (visitscotland.com/surprise), Undiscovered Scotland (undiscoveredscotland.co.uk), Wilderness Scotland (wildernessscotland.com).

First published in The Times, March 31 2012

Great British Weekend: the south Cotswolds

Dr Edward Jenner’s House

Just round the corner from Berkeley Castle, where Edward II is said to have met a nasty end courtesy of a red hot poker (in 1327), we came to a place where another Edward helped save hundreds of thousands of lives over the years.

In the garden of Dr Edward Jenner’s House, we reached a curious thatched hut in which Dr Jenner (1749-1823) vaccinated the poor of the district against smallpox after pioneering the science of immunology. Smallpox, which Jenner called the Speckled Monster, killed one in ten of the population during his time, and his vaccine was the crucial breakthrough. “He saved more lives than any other man on earth,” said one of the museum’s staff.

Jenner is buried in the church of St Mary the Virgin, by the museum. A simple inscription on a vault on the north side of the altar gives the year of his death and there is a window in his memory. It is an elegant church with many murals painted on the walls — some of which looked in need of restoration.

The south Cotswolds — the area south of Stroud with the small town of Nailsworth at its centre — is a far cry from the twee Cotswolds that most people know around Stow-on-the-Wold and Chipping Norton. It is a working community with tourism as an extra, unlike, say, the holiday honeypots of Upper and Lower Slaughter.

Nailsworth bustled with activity. We browsed in independent clothes shops, picked up sausages and bacon in a lovely old butcher’s, and discovered William’s Fish Market and Food Hall — a first-class fishmonger’s with a smart oyster bar at the back. Then we went to the Weighbridge Inn, near an old cloth mill. It is famous for its “two in one” pies and they were superb, served in a room with a blazing fire and a beamed ceiling to which hundreds of old keys had been attached. One half of the pie contains vegetables and the other steak and mushroom, or chicken, ham and leek. They come in various sizes and ingredients which can be customised to suit.

Well fed, we explored the nearby village of Minchinhampton — known locally as “Minch” — with its rows of small terraced houses and its pretty church. A fire was crackling in a corner of an antique shop called the Trumpet, full of Art Deco plates, silver cutlery, and roll-top desks.

“This area was the engine room of the clothes industry,” said Mick Wright, co-owner of the Trumpet with his wife Fanny. He wore leather trousers (he’s a motorbike enthusiast) and a dog collar (he’s also a priest). “Historically the south of the Cotswolds has always been more working class than in the north.”

We were staying on the edge of the village of Nympsfield, just outside Nailsworth, close to Woodchester Park. This estate is owned by the National Trust and has a half-built 19th-century Gothic manor at its centre, complete with marvellous gargoyles. The manor was abandoned mid-construction in 1873 and its rafters are now home to bats.

It is great walking territory. After a long stomp, we made our way to the Rose and Crown where we found hunting folk, in a jolly state, singing songs with dead birds poking out of their jacket pockets. They were local farmers and tradesmen. “Welcome to the madness,” said the landlady as she stoked the fire — no Chipping Norton set during our visit, down in the south of the Cotswolds.

Need to know

Where to stay

The Bellhouse is a house which sleeps eight on the edge of Nympsfield offered by Rural Retreats (01386 701177, ruralretreats.co.uk), with a large dining room and a lounge with a wood fire; three nights cost from £648. Egypt Mill (01453 833449, egyptmill.com) is a comfortable hotel with rooms with exposed beams in Nailsworth; B&B doubles are from £105.

Where to eat

The Weighbridge Inn (01453 832520, 2in1pub.co.uk), between Nailsworth and Minchinhampton, is renowned for its excellent pies, small (£11.40) and large (£14.80), in a building with sections that date from the 17th century. It also serves a good selection of real ales and wines. The Salutation Inn (salutationinn.biz) is a cosy pub in Berkeley, popular with local hunters; good bangers and mash with gravy (£5.75).

Further information

cotswolds.com

First published in The Times, January 5 2013

Gothic manor at Woodchester Park

Great British Weekend: North Pennines, Cumbria

Down by a little pedestrian bridge across the narrow waters of the River South Tyne — near to its source — there is a scrabbling in the bushes. We peer in, wondering if it is a bird of some sort, but it is the bright eyes of a red squirrel that look back at us. It is only our third encounter on the South Tyne Trail all morning and is the first red squirrel that any of us — all city dwellers — has seen.

The North Pennines, part of Cumbria, is one of the few places in Britain where red squirrels survive. Few people visit the area, to the east of the M6, which makes it feel quite distinct from the sometimes twee tourist world that makes up much of the Lake District. It is also one of the best parts of Britain for rambling — even in winter — with plenty of well-marked trails, such as the one where we meet our red squirrel.

Our walk begins in Alston, the highest market town in Britain at just over 1,000ft. Setting off from behind the local youth hostel, we walk through muddy fields before dipping down to the tea-coloured river, with a cliff-face running along the southern bank and mini-waterfalls. After crossing through Garrigill, a one-pub village, we come to bigger waterfalls and a bridge where friends are waiting to pick us up.

Back in Alston we sample Black Sheep ale at the tiny Angel Inn, with its cute Jack Russell , rows of fishing trophies and slightly sloping walls dating from 1611. We buy plump Cumberland sausages from the butcher and then are tempted by another ale at the cosy Turk’s Head pub, next to the market square.

Pubs and inns after walks become an established part of our weekend in this bewitching countryside. Alston is about 12 miles from our base in the tiny village of Glassonby, in the Eden Valley, about six miles east of Penrith. The landscape up to the top of the mountains looks beautifully bleak, and at Hartside summit (1,903ft) there are terrific views across the rolling landscape.

From Glassonby it is a two-mile walk to Kirkoswald along deserted lanes. Kirkoswald is a former market town but is now known for its “mild recreation”, according to a village sign. We find some of the latter in the excellent and popular Fetherston Arms, overlooking the old stone market cross. Its “pie nights” are famous for miles, attracting as many as 80 people each time. They are very good pies.

We are the only visitors to the intriguing Long Meg and her Daughters, a 350ft Druids’ circle and the second biggest in the country. This is near Melmerby, where we recommend the Shepherds Inn, another cosy pub (we get to know a few of them).

On one day we drive to a section of Hadrian’s Wall that runs between the villages of Banks and Gilsland, passing Birdoswald Roman Fort. After a minor altercation with a farmer over parking, we head off through thick mist and fields full of bullocks (not bulls, despite our townie worries), sheep and cows. It is a wonderfully quiet section of the wall that none of us has seen before.

Afterwards we pop into Penrith’s Saturday market, full of bric-a-brac as well as stalls selling hamburgers with pineapple slices and cheese (popular locally). I find a nice framed L. S. Lowry print for £8.

To wind up our stay we pop back to the pub — the Fetherston Arms. And why not? That’s what you just seem to do on a walking holiday in the North Pennines … your feet just seem to take you there.

Need to know

Where to stay Rural Retreats (01386 701177, ruralretreats.co.uk) has three self-catering cottages in the village of Glassonby, each with fireplaces and modern interiors. Two-night stays start at £344 with a welcome hamper.

Where to eat The cosy Fetherston Arms (01768 898284, fetherstonarms.co.uk) in Kirkoswald has two courses from £14. Or for a Michelin-star treat, Sharrow Bay (01768 486301, sharrowbay.co.uk) overlooking Lake Ullswater, has three-course set lunches from £35.

What else to do Visit Sleddale Hall to see the building that the characters from the cult film Withnail and I retreat to for a weekend.

More information visitcumbria.com

First published in The Times, November 26 2011

Great British Weekend Ambleside, Cumbria

Mine was the only car in the small car park of Rydal Mount House, on a hill on the edge of Ambleside. I passed a sign that said that William Wordsworth lived here from 1813 to 1850, bearing his words: “I often ask what will become of Rydal Mount after our day. Will the old walls and steps remain in front of the house and about the grounds, or will they be swept away with all the beautiful mosses and ferns and wild geraniums and other flowers. . . ?”

Well, they’re all still there — old walls, steps, mosses, wild geraniums, daffodils, the lot. I entered the stately white building, where Wordsworth published the final version of his poem Daffodils and found that the rooms have also been kept more or less as they were during his time. A portrait of Robert Burns hangs exactly where it did in the dining room. Wordsworth’s tatty sofa is in the drawing room, next to a picture of the poet from 1844, when Queen Victoria made him Poet Laureate. Through windows next to his favourite armchair, Windermere glistened beautifully in the distance.

After seeing the bedrooms and neat attic study, and learning that the house is still a “lived-in family home for the poet’s direct descendants”, I bumped into John, who wore a Rydal Mount badge. Was he one of the descendants? No, he wasn’t. “I’m missing a vital factor for that: a conk,” he replied — pointing to another portrait of the poet (who did, indeed, have a very large nose).

I looked around the pretty gardens and then drove the short distance back to Ambleside, where I soon found myself walking among people wearing hiking boots and sleeveless jackets with lots of pockets, and carrying rucksacks, passing shop after shop selling hiking boots, sleeveless jackets with lots of pockets and rucksacks: Ambleside is one of the best places in the country for picking up outdoor gear. There were also a lot of inviting pubs with sloping walls, and cosy cafés with funny names (the Giggling Goose, perched by a gurgling tea-coloured stream, looked particularly inviting).

Next to a curious factory-outlet crystal shop — crammed with enormous pieces of amethyst — I found the tourist office, where I asked about local walks. “Stock Ghyll waterfall; you start behind the Barclays bank,” a staffer replied matter-of-factly. I ventured behind Barclays, up a lane and through a peaceful glen filled with trees, with the tea-coloured stream at the bottom.

The sun came out and pools of honey-coloured light filtered down as I walked up a leaf-strewn path to a bridge next to the splashing water of the falls.

Hikers were eating packed lunches at picnic tables. A roar sounded above and a slither of silver slipped above the canopy of trees; a fighter jet doing target practice at nearby RAF Spadeadam, no doubt.

Down the hill — the walk took 40 minutes — I went back through Ambleside, population 2,600, passing along little lanes, and then bigger ones to the edge of Windermere. At the Wateredge Inn a long queue snaked out of the entrance. I waited for a decent sandwich and a pint, sitting on a bank next to the almost still, gently undulating water that Wordsworth used to “sweep along the plain . . . with rival oars” in search of “an island musical with birds/ That sang and ceased not”.

So say the lines in The Wordsworth Poetical Guide to the Lakes (£3.95 from Rydal Mount House), which neatly breaks up his verse according to parts of the Lake District. Back in the “little rural town” where “beams of orient light shoot wide and high” amid the throng of hikers, I stopped in the tiny, and slightly dingy, Armitt Museum. It turned out to be a gem, with displays of art by Kurt Schwitters, an avant-garde German who escaped the Nazi regime and ended up settling in Ambleside and establishing a form of art known as merz, a style of “collage that expresses thoughts and emotions with other materials than just paint, including driftwood from the lake”.

I never knew that before — and I took in his curious abstract works as well as some striking portraits of local characters and landscapes. Schwitters used to sell these to tourists while sitting on the steps of the nearby Bridge House, a funny little structure built over one of Ambleside’s streams more than 300 years ago and now run by the National Trust (it’s one of the most photographed spots in the Lakes).

There were also displays explainingthe town’s links with Beatrix Potter, Charlotte Brontë, Thomas Carlyle, the 19th-century social reformer, Harriet Martineau and Woodrow Wilson, the US president — Ambleside seems to have attracted all sorts over the years. It may no longer quite be the “little rural town” of Wordsworth’s day, but it is still packed full of Lakeland charm.

Tom Chesshyre is the author of To Hull and Back: On Holiday in Unsung Britain (Summersdale, £8.99)

Need to know

Where to stay The Best Western Ambleside Salutation Hotel (01539 432244, bestwestern.co.uk) is in the centre of town with comfortable rooms and a friendly atmosphere, a neat basement swimming pool and a new spa. B&B doubles from £96.

Where to eat The Glasshouse Restaurant (01539 432137, www.the glasshouserestaurant.co.uk) is in a lovely converted 15th-century mill;

sandwiches £5 for lunch, and Cumblerland sausage with red cabbage and mash from £10.

Getting there Thetrainline.com has Euston-Lancaster returns from £36 and it offers Avis hire cars from Lancaster, about 30 miles south of Ambleside, from £19 a day.

First published in The Times, June 11 2011

Great British Weekend: Bradford

I have eaten a fair few curries in Britain in my time. I’ve sampled the best of Brick Lane. I’ve parted with wads of cash at the excellent Bombay Brasserie in Kensington. I’ve tried all my local establishments (naturally), and am a big fan of Bristol’s spicy offerings. But I ate my very best British curry recently in Bradford.

Mumtaz was nothing short of marvellous. And easy to find: up the Great Horton Road and turn right at a tree wrapped in twinkling Christmas tree lights.

After being led through the stylish, modern interior to a corner seat, I was fed spicy poppadums with the finest chutneys, pickles and coriander dips. Next came perfect chicken boti (marinated in delicate spices), followed by a flavour-packed king tiger prawn makhani cooked with tomatoes, pistachios and almonds.

The restaurant is unlicensed, so I drank mango lassi, a terrific smoothie that brought the spices to life.

“Look around you,” said Mumtaz Khan, the owner, originally from the Pakistani part of Kashmir, who started his business aged 22 in 1978 in a tiny stall and is now a multimillionaire selling sauces to supermarkets nationwide. “See all the groups of Asian women? They cook curries every day. They would not be here if we did not do it right, hey!”

Bradford is, of course, a very multicultural city. It also makes an intriguing weekend break, with curries themselves a big enough allure for me; there are endless restaurants from which to choose. And then there’s the fine Victorian architecture in the city centre.

City Hall, for example, is a huge structure adorned with statues of 32 monarchs and with an imposing clocktower said to have been based on the one at the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence. “We call it the little Big Ben of Bradford,” said Simon, the manager of my hotel, the Great Victoria, another splendid Victorian building.

Splendid Victorian buildings are everywhere. My favourite is the old Wool Exchange, now with a Waterstone’s bookshop on the ground floor. On the exterior there are sculpted heads of the likes of Palmerston and Gladstone. Inside there is a giant space with pink marble pillars leading up to skylights with strange Masonic symbols.

On the outskirts of town I went to Cartwright Hall, a sturdy Victorian art gallery, and then to Undercliffe Cemetery, one of the finest Victorian Gothic cemeteries in Britain. Obelisks, grand columns, statues of angels and urns on plinths abound. And there’s a sweeping city view, with moors framing the horizon.

For those who wish to travel farther afield Haworth, with all its Bront? connections, is close by – and there are miles and miles of those moors for walkers.

Back in town the National Media Museum has early TVs and a cinema that David Puttnam has described as Britain’s best. Near the entrance, there is a statue of local-born J.B.Priestley, wearing an almost comical flowing cape.

A quote from the great British observer describes a fictional town based on Bradford, saying that the city is “grim but not mean” and should “not only be tolerated but enjoyed”. Just as I did.

Need to know

Bed down at . . .

The Great Victoria (01274 728706, www.tomahawk hotels.co.uk) had a modern revamp three years ago. There’s a lively-ish bar and a reasonable restaurant. Lots of lawyers stay here, because it is opposite the law courts. David Cameron once held a Shadow Cabinet meeting at the hotel. And Charlie Chaplin once bedded down for the night. The best rooms are on the fourth floor. Doubles from £59, B&B. The Midland Hotel (01274 735735, www.peelhotels.co.uk) is not as fancy and rooms are more expensive. Doubles from £90, B&B. There is also a budget Etap (www.etaphotel.com).

Chow down at . . .

Mumtaz (01274 571861, www.mumtaz.com) is not to be missed: make sure you book. You can buy gift-wrapped boxes of sauces and spices at a small shop. £18 for two courses.

Secret spot

Bombay Stores (www. bombaystores.biz) is Britain’s largest Asian department store selling saris, bangles, pashminas, cloth and jewellery.

First published in The Times, March 21 2009

Great British Weekend: Pluckley, Kent

As we stood by the map at the centre of Pluckley, a sleepy village on a hill with about 1,000 residents on the edge of the Weald of Kent, we felt a presence. It was as though somebody was peering in our direction.

We read the information board connected to the map. “This area has 12 official ghosts as well as many that are less well known,” it said. For a moment or two we felt as though one of them had joined us. Then we realised what it was. Behind the branches of a tree in the front garden of the cottage before us was a scarecrow, with a twisted shape and spooky eyes — seemingly leering our way.

With that introduction to Pluckley, which was named as the most haunted village in England by the Guinness Book of Records in 1989 (and if Guinness says so, it must be true), we proceeded to one of its most ghostly spots.

The church of St Nicholas is said to be haunted by several spirits, including The Red Lady and The White Lady, both believed to be versions of Lady Dering, a local noblewoman. She is said to have been buried in parts, in seven lead coffins, when she died in the 12th century (real-british-ghosts.com says this, so it must also be true).

We walked around the imposing stone church with its slanting gravestones and its steeple that looks a little like a witch’s hat. At the back there was a gate that led through to a pretty apple grove. It was a beautifully bright October day with a royal blue sky and not another soul around — at least none that we could see.

Inside the church, we took in the big stone arches, rafters, old-fashioned enclosed pews and a pile of fruit and cans of soup collected for harvest festival. A fun, colourful map celebrating the Millennium showed the village with the Eurostar zooming along the bottom; Pluckley is not far from Ashford, one of the fast train’s stops. It was a lovely old church, with no one else around. There were no flickering lights, no clanking chains, no strange murmurings, no Red or White Ladies — just the gentle sound of birdsong outside.

Pluckley looks down from its hilltop perch on flat fields and orchards in one of the most peaceful parts of Kent. We took a look to see if we could catch a glimpse of the Watercress Woman, the ghost of a Gypsy who apparently burnt to death after her pipe set fire to the alcohol that she was drinking while she was selling watercress down by Pinnock stream. She wasn’t there, but there was a lot of mist about, early on Saturday morning — a sign that she may have been there recently (so says mysteriousbritain.co.uk, so it must be true).

We couldn’t find the Highwayman either, said to haunt the nearby Pinnock Crossroads, also known as Fright Corner. Pluckley’s Screaming Man — the spirit of a man who was smothered when a wall of clay collapsed on him in a local brickworks — was nowhere to be seen either. Nor were the many ghouls and troublesome poltergeists of the Black Horse pub making themselves known, although decent pints of bitter were on tap. We were staying at Elvey Farm, a remote guesthouse with a well-regarded restaurant and nine rooms set in seven acres just to the southwest of the village centre. It, too, is said to be haunted, by the ghost of Edward Brett, a farmer who shot himself near the dairy in the 1800s (so says Simon Peek, one of the owners).

Brett is said to have whispered “I will do it” to his wife before he carried out the deed — and guests sometimes hear these words whispered in the wind late at night.

We drank wine from the nearby Biddenden Vineyards, and ate a fine meal of potted ham with Kentish huffkin (a crusty bread) and hunter’s game pie, washed down with more Biddenden wine.

Then we walked along a dark gravel path in England’s most haunted village, hoping that the wine might bring out the ghouls. But still no apparitions. The ghosts must have been having a day off … saving it all up for Hallowe’en, perhaps.

Need to know

Bed down at Elvey Farm (01233 840442, elveyfarm.co.uk) has B&B doubles from £100, B&B suites are from £150. Dinner B&B packages for a night are available for £156. The small bar and restaurant are cosy and candlelit, and had a busy, jolly atmosphere on the Friday night of our visit.

Chow down at Apart from the restaurant at Elvey (open to non-guests), there is decent bar food at the Black Horse in the centre of the village. Or buy a picnic from the Pluckley Farm Shop on Smarden Road — lots of fresh bread, jams, fruits and juices, mostly produced locally. Also, try visiting Biddenden Vineyards (01580 291726, biddendenvineyards.com) in nearby Biddenden for superb English wines, jams, chutneys and local beers.

Find more at Visit Kent (visitkent.co.uk), and check out the sections on Pluckley in the websites mentioned in the article.

First published in The Times, October 30 2010

Great British Weekend: Cockermouth, Cumbria

When the banks of the Cocker and Derwent rivers burst their banks, causing terrible flooding in the centre of this pretty market town on the northwest edge of the Lake District on November 19 last year, Sue Eccles, manager of the Trout Hotel, did not know which way to look.

At the back of her well-run hotel, which had just been awarded four stars by the tourist board, Eccles had been watching the waters of the Derwent rising.

“We’d seen this before and we were not so worried to start with,” she told me in the smart bar of the Georgian-fronted hotel that reopened in June after having restoration and refurbishment works costing almost £4 million. “But then someone said that water was also at the front of the building.”

This second flood had been caused by the Cocker bursting its banks. This was not normal. Soon parts of the centre of Cockermouth were submerged in up to 2.5 metres (8ft 2in) of water. Almost all the guests were evacuated from the Trout.

The nine remaining guests, plus 17 staff, made it to the first floor. Dry food, candles, bottled water, plus a sound supply of beer and wine were rushed upstairs, as were the hotel’s computer hard drives. They watched events unfold on television until the electricity cut out at 9pm. By then, the hotel was an island.

Visiting Cockermouth earlier this month I was staggered by the speed with which many businesses, the Trout included, had reopened after the heavy flooding. Walking along the main street, many shops were still boarded up, with signs saying “Dangerous Structure”, while others had builders on site making repairs. But so much of the town is up and running once again, and there is a tangible sense of camaraderie that has come from adversity, with so many people, like Eccles, having dramatic stories to tell about that harrowing day — and being happy to relate them to outsiders.

Next to the Trout you will find Cockermouth’s big attraction: Wordsworth House, where William and Dorothy Wordsworth were brought up. It is a large terracotta-coloured Georgian building that also suffered from the flooding, with the front gate being swept away and a terrace at the back, where William and Dorothy used to chase butterflies, almost totally destroyed. Fortunately, the entrance level is raised.

“The water got to within an inch of the floorboards: it was that close,” said Rachel Painter, the house steward at the National Trust property. “Apparently, the Environment Agency is dredging the rivers and reinforcing flood defences so it will never happen again.”

It’s interesting to see the house where William lived until the age of 13, when his father died, and to look out across the herb and fruit garden towards the river Derwent. “Was it for this/ That one, the fairest of all rivers, lov’d/ To blend his murmurs with my nurse’s song,” he wrote in The Prelude (1805).

Walking along the main street, I see that book shops, pubs, gift shops, restaurants and antique stores have all reopened. At CG’s Curiosity Shop, which is next to the bridge over the river Cocker and full of porcelain collectibles, old medals, antique cameras and bits and bobs, Colin Graham, the owner, said: “I wasn’t insured — I could never afford the insurance. I lost everything.” He reopened a few days before my visit and has good-humouredly hung a life ring behind the checkout till.

After finding the grave of John Wordsworth, William and Dorothy’s father, at the pretty All Saints Church, I walked to Jennings brewery, down by the river Derwent. This fine old brewery has been producing real ales at this spot since 1874 and you can take tours that culminate in a beer-tasting at a little on-site pub; pints of Cocker Hoop, a “golden bitter with a classic hop flavour”, are being downed gleefully on my visit. The brewery was damaged badly in the floods and has been completely refurbished downstairs.

The bed in my room at the Trout would have been under water in November. But now it is stylish, comfortable and with a lovely view of Wordsworth’s fair and murmuring river — even if it did murmur a little too loudly last year.

NEED TO KNOW

Bed down at . . . The Trout (01900 823591, trouthotel.co.uk) on Crown Street has two nights’ dinner and B&B from £149pp. There’s parking, a cheery bar, and a bistro. Rooms and public areas are decorated with pictures of Lake District landscapes. Six Castlegate (01900 826786, sixcastlegate.co.uk) is in a Grade II-listed Georgian house on a hill that was not affected by the floods — B&B doubles from £65.

Chow down at . . . The bistro at the Trout has hearty food such as steak and Jennings ale pie (£9.95), Cumbrian griddled sirloin steak (£15.95) and pizzas (£8). Quince and Medlar (quinceandmedlar.co.uk) is a popular vegetarian restaurant next to Cockermouth Castle.

Secret spots . . . Castlegate House Gallery (castlegatehouse.co.uk) is a superb art gallery in a Georgian house on the hill above Jennings Brewery, displaying some of the best works capturing the scenery in Cumbria; there’s a pretty garden at the back with elegant sculptures.

First published in The Times, August 28 2010

Great British Weekend: The Rhinns of Galloway, Scotland

To the south I can see the Isle of Man, a distant, undulating shape that looks like the body of a giant sea monster. To the west there is the thin grey strip of Ireland and the Wicklow Mountains. And to the northwest, on an even thinner strip of land beyond orange-tinted cliffs, lies Belfast. It is quite a view. I am at the Mull of Galloway, the southernmost point in Scotland and the southernmost point of the Rhinns of Galloway, a peninsula that drops so far south it is level with Penrith in Cumbria.

The views are one thing (a superb little café with a grass-covered roof and haggis bagels for £3.95 allows you to enjoy the scenery, whatever the weather) but the peninsula also has one of the finest and most unusual collections of gardens in Britain. After admiring the lighthouse, I drive along twisty roads to the Logan Botanic Garden and feel as if I have entered another world. The Gulf Stream and the peninsula’s narrow tip mean that temperatures here are usually about 2C warmer in the winter — and 2C cooler in the summer. The result is an extraordinarily exotic, 25-acre garden of plants from the Far East, Australasia and South America.

Rows of cabbage palms with peculiar branches are interspersed with curious 130-year-old tree ferns from New Zealand. A neat row of Chinese palms stands near a pond surrounded by purple drooping flowers known as “angel’s fishing rods”. Beyond are eucalyptus trees usually found in the Australian Outback, the red-flowered pohutukawa (New Zealand Christmas tree), Mexican jelly palms, and banks of pink Vietnamese rhododendrons.

I take in the nearby Ardwell Gardens, a secretive place full of yet more palms and rhododendrons. Then I visit the lovely Dunskey Gardens at Portpatrick, a few miles up the coast. This is another hidden spot, with lily ponds, palms, Andean trees and lochs full of rainbow trout (a day’s fishing permit is £15). Orr Ewing, Dunskey’s friendly owner, says: “Everyone drives past this part of Scotland going to the Highlands: they’re missing out.”

I agree. My hotel overlooks the charming little port at Portpatrick, once the main departure point for English troops supporting the Plantation of Ulster in the 17th century. It was the most important local port to Ireland, only 17 miles away, until the 1860s when ships moved to the more protected harbour at Stranraer. Portpatrick reverted to fishing … and tourism. Now there are fine seafood restaurants, a golf course, cosy pubs, shops of collectibles, and a little sandy beach. The port (population: 600) feels tucked away; with the lights of Ireland twinkling at night across the water, it’s a perfect hideaway for a quiet couple of days.

Need to know

Bed down at . . .Fernhill Hotel (01776 810220, mcmillanhotels.com) has HB doubles from £148. Or try the Waterfront Hotel (01776 810800, waterfronthotel.co.uk) with simple B&B sea-view doubles from £50.

Chow down at . . .The Waterfront serves local lobster, sea bass, hake and scallops. The café at the Mull of Galloway serves excellent sandwiches.

Secret spots . . .Logan Botanic Garden (rbge.org.uk), Dunskey Gardens (dunskey.com), Glenwhan Gardens (glenwhangardens.co.uk) See visitscotland.com

First published in The Times, August 21 2010

Great British Weekend: Adlestrop, Gloucestershire

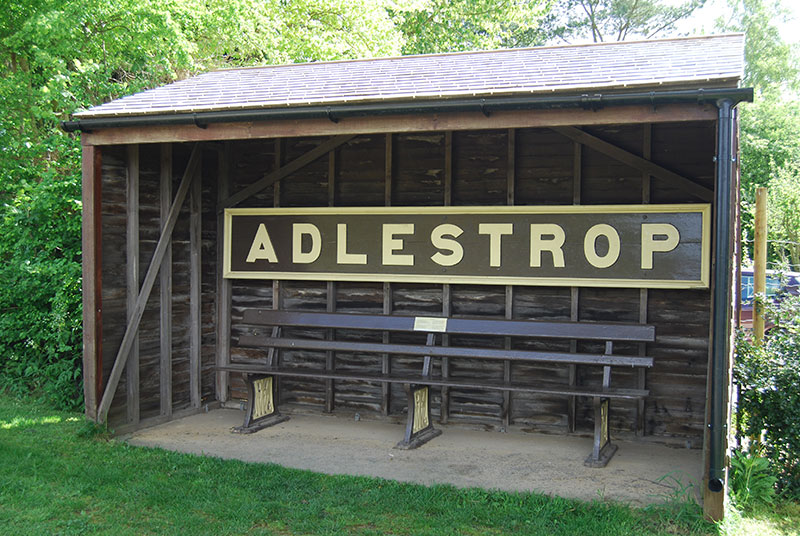

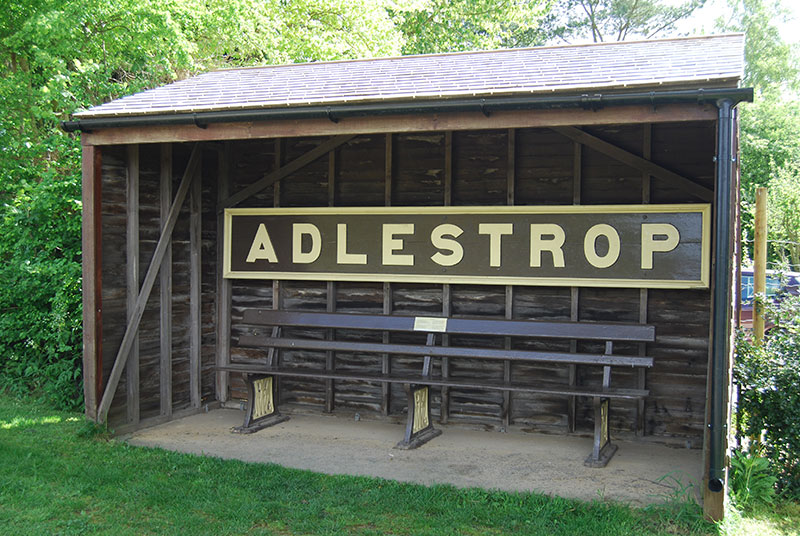

Old railway sign at Adlestrop

Beneath a venerable old oak tree in a sleepy village (population about 80) in the Cotswolds, a small group of ramblers had gathered by a bus stop. It was a hot day in early June, with birdsong, bright sunlight and a sense of quiet across the countryside. The ramblers were pausing for a rest by a big brown and gold former railway sign that said “Adlestrop”, set within the bus stop.

I asked one of them if they were making a pilgrimage to the village that inspired the well-known poem entitled Adlestrop by Edward Thomas, the poet who died at 39 in the First World War. In the poem Thomas evocatively describes passing by Adlestrop’s little railway station (long since shut down) and gathering his location from reading one of the signs.

“I haven’t heard of that,” said one, looking up the lane to where the station had been. “Oh, yes — I hadn’t thought of that: was it here?” said another.

They may have forgotten Adlestrop – with its famous first line, “Yes, I remember Adlestrop” – though others hadn’t. In the poem, the hissing express train makes an unscheduled stop by the village station on a late June day, with “high cloudlets in the sky”. This is now depicted in a mural in the village hall, beyond which is a row of wisteria-covered cottages leading up a lane to the post office.

“On a weekend we might get 60 people passing through,” said Richard Price, who mans the post office and whose father was the last station master. He explains that most are walkers (it’s beautiful walking country, with lots of trails). Price has Adlestrop cards for sale, very tasty home-made sandwiches and a gold-framed version of the poem (£12). He says that it’s sad that the station closed because it has cut off the village, but that the locals are proud of the poem.

Up a small hill we come to a pretty stone church where Jane Austen’s mother’s cousin was once rector. Austen, apparently, visited many times. No one else was about and it felt a very tranquil spot. Afterwards we drove about a mile to the Daylesford Organic Farmshop. It was not so calm and quiet here; the car park was packed with shiny BMWs, Range Rovers, Porsches and classic cars — business is clearly booming.

Inside were row upon row of freshly picked vegetables, and all kinds of food, including lobsters on crushed ice. And all of it organic, in line with the growing Daylesford chain’s ethos of sustainable farming without pesticides (which, we notice from the prices, does not come cheap). The company that began round the corner from where Thomas stopped in his train “one afternoon of heat” has outlets in Pimlico, Notting Hill and Selfridges, in London.

We have an organic coffee in the gravel yard amid the BMW, Porsche and Range Rover owners before driving another short distance to Stow-on-the-Wold. This is a pretty market town on a hill, and although A. A. Gill in his book The Angry Island described it as “catastrophically ghastly” and “the worst place in the world”, it seemed nice enough to us, with its pretty stone buildings and ivy-covered old pubs with names such as the Bell Inn and the Eagle and the Child. At the latter, an excellent steak and ale pie with garlic mash is a not so catastrophically ghastly at £12.95.

Adlestrop and its countryside environs have much more to them than a poem these days (if you’re passing by and remember to stop).

Need to Know

Bed down at The Royalist Hotel (01451 830670, theroyalisthotel.com) in Stow-on-the-Wold has comfortable modern rooms and a good restaurant. The Old Post Office (01608 658342, www.oldpostoffice-adlestrop.co.uk) costs from £50 per person per night B&B.

Chow down at Adlestrop’s post office serves good sandwiches, tea and cakes. A piece of cake is £2 and a cheddar sandwich £6.20. Or try the café at the Daylesford Organic Farmshop (daylesfordorganic.com) — parsnip and bacon soup (£6.95), leek, spring onion and cheddar quiche (£8.95), beef lasagne (£11.95).

First published in The Times, July 10 2010

Train passing by Adlestrop

Great British Weekend: Horncastle, Lincolnshire

Driving into this small market town (population 6,000) in the lovely, rolling Lincolnshire Wolds, the first sign we saw said: “Ferrets for sale.” But while ferrets are apparently all the rage among celebrities these days — with Madonna and Paris Hilton adopting them as pets — there is, as we soon discovered, nothing trendy or celebrity about Horncastle. Quite the opposite … and that’s what makes it such a good spot for a weekend break.

For many centuries the peaceful town was famous for its annual August horse fair, and the phrase “Horncastle for horses” came into usage. Such was the fair’s reputation that the horses used by Lord Cardigan in the Charge of the Light Brigade in the Crimean War were bought there (as well as opposing Russian mounts, if local rumours are to be believed). But the last fair was held in 1948, and now Horncastle has another trade for which it has gained fame: antiques.

After considering buying a ferret, we drove past a succession of antiques shops with big glass windows and higgledy-piggledy window displays with porcelain figurines, stacks of old tables and oil lamps to a car park by a stream. We crossed a small bridge and found ourselves in the pretty market square — which smelt deliciously of fish ’n’ chips from a shop on a corner — with fine old buildings, one of which had “HORNCASTLE FARMERS’ CLUB” painted on it in bold letters.

Another, Perkins Newsagents, was a terrific orange-and-black-fronted building from the turn of the 20th century with large, old-fashioned windows and slightly faded framed pictures of aircraft (including Concorde) on sale.

We stopped at the Sir Joseph Banks Centre, with brief displays on the botanist who travelled with Captain Cook on The Endeavour and who was an important local landowner, and then did what you’re meant to do in Horncastle. We hit the (many) antiques shops.

They are quite something. In a shop called Clare Boam, on North Street, we could barely fit in through the door it was so overrun with piles of fine bone china, magnifying glasses, Silver Jubilee mugs, old clocks, brass candlesticks and buckets of yellowing golf balls (50p each). Absorbed, we walked on into another room with great stacks of LPs (Beethoven next to Johnny Cash and Run DMC), desks and old fireplaces.

This opened into a vast cobbled courtyard filled with trestle tables piled almost comically with china collectibles. Beyond were barns and old coach houses packed with old desks, antique chairs, secondhand books, 1970s skis, china Buddhas and cobweb-covered wardrobes. It was an antique lover’s dream. “Actually, we sell antiques, collectibles and contemporary here,” said Clare, who has red hair and a sharp sense of humour. We asked for a discount on a wobbling side-table that had caught our eyes. “That’s character building, that is,” she said, testing the wobble and grinning.

After checking out a few more shops — we could have browsed for hours — we drove into the nearby sleepy village of Somersby. This is where Alfred, Lord Tennyson was brought up. His father was the rector at the delightful St Margaret’s Church, and Tennyson was raised in the distinguished cream building opposite. So, after seeing the source of the horses from the Charge of the Light Brigade, we had discovered the origins of its famous poem.

Peter Skipworth runs local tours and he took us down a hill to the stream that was the inspiration of the poem containing the famous “babbling brook”. He told us: “Almost nothing is made of Tennyson here.” Indeed, apart from a couple of cabinets containing his quills and pipes in the church, there is very little. “Compare that to the Isle of Wight, where he lived later, and the fuss made of him there.”

At his father’s grave in the churchyard, Skipworth also told us that the poem Come into the Garden, Maud was based on Tennyson’s love for a daughter of the family living at nearby Harrington Hall. Then he admitted: “I almost feel guilty telling you all this in case lots of people come.” With walks in the Wolds and the seaside delights of Skegness and Mablethorpe not that far away — and the chance to buy a ferret — there is more than enough to do on a weekend away in Horncastle.

Need to know

Bed down at . . .

Poachers’ Hideaway (01507 533555, poachershideaway.com) is just northeast of Horncastle near the village of Belchford, and has well-maintained cottages and beautiful views across the Wolds; three nights in a cottage with a double bedroom from £200. Admiral Rodney Hotel on North Street (01507 523131, www.admiralrodney.com) in Horncastle has doubles from £70.

Chow down at . . .

Longfellows restaurant (01507 522722) which is also on North Street, has a cheap and cheerful menu with salads, burgers and baguettes.

What to see …

Tattershall Castle (01526 342543, nationaltrust.org.uk), eight miles south-west of Horncastle — a red-brick medieval castle built by Ralph Cromwell, Lord Treasurer of England.

First published in The Times, May 15 2010

Great British Weekend: Cookham, Berkshire

There are two ways of seeing Cookham — with your own eyes and through those of its famous local artist Stanley Spencer (1891-1959), who painted vivid pictures of the pretty village nestled by a quiet bend of the Thames in Berkshire. I enjoyed both … but I think I preferred the latter.

After driving along the A4094 from Maidenhead, I waited at traffic lights before crossing the sky-blue curve of an elegant Victorian bridge into Cookham. The views were of the sun-dappled Thames, grass banks and countryside.

On the far side there was a glimpse of the tower of a stone church (Holy Trinity), a cosy-looking pub (the Ferry), and a tree-lined lane between distinguished houses leading to a small street with little florists, tearooms and more pubs.

It was all quite delightful. But it seemed even more so inside the whitewashed former Methodist chapel on the corner of Cookham’s main street, known as The Pound. This art gallery, the Stanley Spencer Gallery, opened in 1962, houses a superb selection of his works — from slightly doleful self-portraits to a bright array of pictures depicting local scenes, many capturing the quiet of boats on the Thames, characters working peacefully in boatyards, and verdant gardens tumbling with flowers.

The centrepiece of the gallery is a huge half-completed painting entitled Christ Preaching at Cookham Regatta, which shows Christ wearing a peculiar hat, leaning forward in a wicker chair while dozens of figures listen on punts, boats and riverbanks amid cavorting and carousing. Why was the painting never finished, I asked a volunteer? She replied smartly, with a smile: “Because he was tactless enough to die.”

Spencer was nicknamed “Cookham” while at the Slade School of Fine Art in London since he painted so many local scenes and “thought Cookham was heaven”, said the volunteer. The gallery is small but packed with colour, so much so that going outside again seemed a bit of a letdown. But not for long. After considering popping into the Bel and the Dragon, which dates from 1417, I stopped off at the White Oak pub, which is, so the tourist board advised, owned by Terry Wogan’s daughter, Katherine.

There I ate a fine tagliatelle with wild mushrooms in a room painted in shades of grey and magnolia, while candles flickered and Amy Winehouse played on the stereo. There was no sign of Katherine or her father. Then I strolled back along the river, and drove to Cliveden on the other side of the sky-blue bridge. This is a National Trust garden on a hill with marvellous views of the Thames, with a first-class hotel in the Italianate former country house of the Astors.

Here, John Profumo, the British Secretary of State for War, met Christine Keeler, a 19-year-old model and showgirl, by the swimming pool (which is still there) in 1961. Keeler was linked with a Russian spy and her affair with Profumo led to his resignation. This is a fine country house hotel, with traditional decor (coats of arms, vast fireplaces, antiques, oil paintings, doormen in tails who park your car), and a modern spa next to the pool. The sweeping views from the back terrace across immaculate landscaped gardens to the Thames rival those of the river at Richmond Hill.

It all feels very grand compared with Spencer’s homely take on quiet country life in Cookham. Political sex scandals up on the hill, while life down near the old boatyards has not changed all that much since the much-loved artist’s day.

Need to know

Bed down at Cliveden (01628 668561, clivedenhouse.co.uk) offers B&B doubles from £276. Or try the smart Compleat Angler (0844 8799128, macdonaldhotels.co.uk) in Marlow, B&B doubles £112.

Chow down at The White Oak (01628 523043, thewhiteoak.co.uk) has two courses for about £22. Friendly service.

More information Tourism South East (visitsoutheastengland.com). Stanley Spencer Gallery (stanleyspencer.org.uk). Entry £3.

First published in The Times, February 6 2010

Great British Weekend: Grange-over-Sands, Cumbria

There is a crisis in Grange-over-Sands: the sands have disappeared. A little more than a decade ago tall grass began to grow on the sand flats that stretch into Morecambe Bay and give the south Cumbrian village, which became a fashionable seaside resort in the 1850s, its name. Now, instead of a romantic expanse of creams and yellows, there is a bed of emerald green. Perhaps, as some local wags have suggested, the place should be renamed Grange-over-Grass.

It is a mystery how it happened, says Stephen Tyson, who runs the charming Over-Sands Books, a second-hand bookshop at the tiny railway station, which looks across the former sands. “It got silted up and raised about 4ft or 5ft, then the grass came,” he says, peering out of his window. This has to be one of the most peaceful (there are few trains) bookshops in the country, with surely the best view. “People who came here ten years ago are amazed: they can hardly recognise the place.”

Schemes are apparently being considered to discourage the grass, but it still looks beautiful, with herons, geese and swallows flickering above and the silvery waters of the bay swirling beyond. After buying The Poems of Coleridge (£6.50, published 1927), I take Tyson’s advice and go for a walk along the promenade towards a distant tearoom.

Along the path, which follows the quaint railway line (everything seems quaint in Grange), there are flowerbeds lined with lavender, roses, daisies, palm trees, heathers and ornamental thistles.

All this is maintained by the local civic society, a sign says. It is a delightful walk, with the expanse of the bay on one side and the well-tended flowers on the other. More signs warn of fast-rising tides, hidden channels and quicksands. There are guided walks across the sands at certain times of year; best to inquire at the tourist office.

The Edwardian-era tearoom is closed, probably because so few people are about. In the village centre, however, there are plenty of open tearooms, and I find myself in At Home, eating a hearty lunch of beef and onion pie, baked potato, broccoli, French beans and carrots, all topped with gravy. It’s just the ticket . . . and only £6.25.

Grange has lots of tearooms, old-fashioned grocery shops, butchers, bakers, ornamental gardens and jewellery and porcelain figurine shops. There are several churches. It is pretty and quiet — which is what makes the village (population 4,000) so special. It does not have the Lakeland bustle of Windermere, Barrow-in-Furness or Keswick — yet all these places are fairly short drives away, making Grange a good base for a relaxed visit to one of the busiest tourist spots in Britain.

“There’s not much nightlife here,” says Elaine Ware, who runs Daisyroots, another second-hand book shop. “Grange is renowned for its good manners and courtesy. It’s an Edwardian resort and it has kept its Edwardian manners.”

Edwardian Grange, a poem written by Helen Western, is pinned to the door of the tourist office. It begins: “Boarding the steamer, the train and the charabanc/ Winding their way through Edwardian grace/ Top-hats and tail-coats, crochet and cross-stitch/ Checked suits, cravats, silk, boater and lace.” Well, the top hats and tailcoats have gone, but the fine Edwardian essence, if not the sands, is still around in Grange.

NEED TO KNOW

Bed down at . . . Netherwood Hotel (01539 532552, www.netherwood-hotel.co.uk) is on a hill a short walk from the station. It is a sturdy Victorian manor house, with elegant gardens and sweeping views of the bay. Rooms are traditionally decorated. B&B doubles from £150.

Chow down at . . . At Home Cafe & Bistro (01539 534400, www.athomecafebistro.co.uk) is at 2 Main Street, serving simple, well-prepared and inexpensive dishes — pies, omelettes, sandwiches, fish, baked potatoes, scones and slices of gooseberry summer cake.

Outside bets Near by is Holker Hall (www.holker.co.uk), the stately home that is the seat of the Cavendish family. The Lakeland Motor Museum (www.lakelandmotor museum.co.uk) is in the grounds of Holker Hall and includes Bluebirds driven by Sir Michael Campbell and his son Donald to break land and water speed records.

First published in The Times, November 21 2009

Great British Weekend: Lower Largo, Fife, Scotland

When Alexander Selkirk was a boy, causing trouble in the tiny fishing village of Lower Largo in East Fife, no one could have guessed at the longevity of the effect of his reckless streak.

At the local church, which was invested with the power to reprimand antisocial behaviour, Selkirk was a well-known figure, considered to have a “quick temper and tempestuous nature”.

That is what it says in a booklet called Crusoe’s Village that I pick up at an arts and crafts shop close to the cottage where the inspiration for Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe was brought up in the late 17th century.

“He was pretty disreputable and he was definitely kicked out of this church,” adds the gardener at Largo Church, a lovely stone building with a spire and a black and gold clock face in Upper Largo (Largo is split into its Upper and Lower parts, despite being very close to each other).

The gardener is too shy to be named, but she puts down her trowel and takes me to the grave of the troublesome Selkirk’s parents, which is surrounded by cockle and whelk shells, to the left of the church entrance. On the sloping, mossy stone you can just make out the family name. “We put the shells here as a tradition,” the gardener says. “It helps mark out the grave. People are always asking about it.”

Selkirk left home in a petulant mood at 19, became a privateer on ships preying on bounties carried by the French and the Spanish, fell out with the captain of his vessel, asked to be left on one of the Juan Fern?ndez Islands (many miles off the coast of Chile) and remained there for four years and four months, living on his own while expecting a ship to pass and save him at any moment. This took a little longer than expected. His story caught the eye of Defoe, and the rest is Robinson Crusoe.

Surprisingly little is made of the famous local connection, other than a bronze statue of Crusoe at the location of the cottage where he was brought up, and the Crusoe Hotel. This is a slightly ramshackle affair with a modern wing, right on the waterfront of the Forth, next to the pier where lobsters and crabs are brought in and served, delightfully fresh, at the hotel’s Castaway restaurant.

“A lot is made of the Loch Ness monster and of Rob Roy. I don’t see why the tourist board doesn’t promote Crusoe’s connection here,” says Stewart Dykes, the hotel’s owner. “People drive by Lower Largo and don’t know what they’re missing.”

In a way, that is for the best, because the village is wonderfully sleepy, with a single pub (the Railway Inn), the hotel and two small shops. Waking up at the Crusoe, with the sun shining on the cerulean expanse leading across to distant Edinburgh, feels incredibly peaceful.

It is also a good spot for exploring East Fife. From the village, which has its own beach, you can walk along the pretty coastline, passing links golf courses and traversing cliffs (the “chain walk” at Elie is quite dramatic).

The Scottish Fisheries Museum at Anstruther is worth a visit, as is the Secret Bunker, an underground shelter near Crail that was once the official retreat for the people who would have governed Scotland in the event of a nuclear strike.

Need to know

Bed down at . . . The Crusoe Hotel (01333 320759, crusoehotel.co.uk) is on the harbour in the shadow of the old railway viaduct. B&B doubles are from £75.

Chow down at . . . The hotel’s Castaway restaurant is reasonably priced and attracts a good mixture of tourists and locals; £20 for two courses. Very Crafty has a cosy “Coffee Corner” serving hot drinks and scones.

Outside bets . . . The Scottish Fisheries Museum (01333 310628, scotfishmuseum.org) tells the story of the heyday of Scottish fishing; admission £6. The Secret Bunker (01333 310301, www.secretbunker.co.uk) is extraordinary and a must to visit; admission £8.90. Visit Scotland (0845 2255121, visitscotland.com/ perfectday).

Get there . . . National Express (0845 7225225, nationalexpress.com) has London to Edinburgh returns from £33.

First published in The Times, October 10 2009

Great British weekend: Knutsford, Cheshire

Not far from a Rolls-Royce showroom, a designer handbag shop, a lingerie boutique and several estate agents advertising million-pound pads popular with Manchester United and Liverpool players, there is a building on King Street in Knutsford that seems to combine Art Nouveau, Gothic, Neo-Classical and Italianate architectural styles. It is dominated by a rocket-like tower with a step-shaped turret.

Halfway up the tower is a bust of Elizabeth Gaskell, who is protected by netting to keep off the pigeons and who gazes serenely down at the Jaguars, Bentleys and Range Rovers moving along the narrow road, many driven by blondes with back-seat piles of shopping.

Knutsford, the East Cheshire town with a population of about 13,000, is a curious mix of fantastical architecture, literary history and conspicuous consumption.

The Elizabeth Gaskell Memorial Tower, which commemorates the 19th-century novelist who lived in the town from 1810 to 1832, seems to symbolise all its competing strands.

The tower is part of a Gaskell trail that takes in many places mentioned in her popular early novel Cranford, as well as the fine Regency house overlooking the heath where she lived, the parish church in which she was married, and her grave at the Brook Street Unitarian Chapel.

The tower was built in 1907 by Richard Harding Watt, a wealthy glove manufacturer, who began designing after being inspired by European architecture.

Now the building houses the Belle ?poque restaurant, once a favourite of David and Victoria Beckham. “That’s what we call Beckham Corner,” says Nerys Mooney, co-owner of the restaurant, which is decorated in Art Nouveau style with bright pink walls. The corner she is referring to is hidden at the foot of the tower, beneath Gaskell’s bust.

“They used to come at least once a week. Posh would visit more often. Footballers are always coming; we’ve had the lot of them. My favourite was Ruud van Nistelrooy: gorgeous and charming.”

Passing jewellery and antique shops, I stroll to the local Heritage Centre — it is easy to walk from one side of town to the other, along narrow streets lined with lots of quaint buildings, in a few minutes.

The centre is small and eclectic, with a beautiful tapestry that was commissioned to celebrate the millennium. It shows almost all the town’s streets in detail, including the whereabouts of Blockbusters and Oddbins. Gaskell’s works are for sale, as is a detailed guide to all the buildings connected with her.

“We’ve had so much interest after the TV series of Cranford,” says Jan McCappin, a volunteer at the centre, who reminds me a little of Miss Pole (from the series).

She adds that more episodes, filmed in Laycock in Wiltshire, not locally, are planned for around Christmas. “Judi Dench [who will be in the new episodes] came round a couple of weeks ago to soak up some of Knutsford’s atmosphere.”

I soak up more of the atmosphere myself as I walk past the basis for the fictional Miss Matty’s Teashop to Legh Road. This is full of giant mansions designed by Harding Watt that you can imagine sitting beside a lake in northern Italy, rather than in east Cheshire.

You can also imagine a few millionaire footballers and WAGs lurking inside. What would Gaskell have made of Knutsford now?

Bed down at . . .

Cottons Hotel (01565 650333, cottonshotel.com), Manchester Road, Knutsford WA16 0SU. This is a comfortable hotel with a large indoor pool, a spa, and a stylish restaurant and bar with a jazz theme. It is slightly out of town, but benefits from a lot of parking and well-designed rooms with free internet. Good breakfasts. Doubles with B&B from £140.

Chow down at . . .

Belle ?poque (01565 632661, thebellepoque.com) offers three-course set menus for £25 of modern Britsh food using local ingredients in its extraordinary bright pink dining room. The room is full of Art Nouveau figures, smoky mirrors and a sense of the extravagant. Book well ahead for Beckham’s Corner.

Stretch your legs

Tatton Park (01625 374400, tattonpark.org.uk), on the outskirts of town, is a must. The country house, run by the National Trust, dates mainly from the mid-18th century and is considered one of the most complete mansions of its kind in Britain.

The 2,000 acre grounds include deer parks and fantastic gardens: many say that the Japanese garden is the best in Europe , while vegetable and fruit plots, the vinery, and the pineapple and orchid houses are marvellously maintained.

The gardens at Arley Hall (arleyhallandgardens.com), near Northwich, are also recommended.

First published in The Times, October 3 2009

Great British Weekend: Dudley, West Midlands

In a pitch-black canal tunnel in a Black Country hill, all is quiet apart from the occasional sound of dripping water.

I’m wearing a hard hat, as are the other passengers on our barge, captained by Steve. He suddenly makes an announcement: “Dudley was once a tropical sea!”

And before this can quite sink in, he explains that tropical remains from millions of years ago created the coal seams here.

This is why the extraordinary network of miles of underground canals was necessary: to provide access to the coal as well as to limestone (we later enter a huge limestone cavern, which Steve informs us is licensed for weddings).

Coal, limestone and iron ore are what brought the region to the north and west of Birmingham its Black Country nickname: the soot from factories during the 19th-century heyday of industrialisation was so extensive that it blackened the land. All this, and much more, we learn at the Black Country Living Museum.

While museums describing industrialisation can be less than riveting, not so at Dudley, where old buildings including terraced houses, swimming baths, a church, a confectioner’s, a fish ’n’ chip shop, a pub and a mine shaft have been recreated brick by brick after being saved from demolition. The result is a complete village over 26 acres; a throwback to life two centuries ago.

Displays are minimal, although there is an interesting section near the entrance that explains how different local towns developed particular manufacturing expertise. West Bromwich, for example, was known for its door knockers and springs, while Smethwick created lighthouse lamps.

Horse irons and leather were a speciality in Walsall. Oldbury was famed for its steel tubes, and Dudley respected far and wide for its anvils, fire-grates and glass. Most manufacturing ended in the 1970s because of competition from the Far East.

There’s another surprise round at Dudley Zoo, perched on a hill bearing the jagged remains of the 11th-century Dudley Castle. The zoo is where the local lad Lenny Henry performed some of his first stand-up comedy, in the cafe near the sea lion enclosure.

Local Sue Lawley also used to work here, serving refreshments in a kiosk. The zoo was founded in 1937, and contains rare snow leopards, Tibetan red pandas, a pair of lions, and an enclosure you can stroll about as Madagascan lemurs leap around you.

I hadn’t expected that in Dudley. Nor did I expect the gem of a museum I found on the edge of neighbouring Stourbridge. The Broadfield House Glass Museum has an amazing collection of glass, much of which was produced locally.

The colours are dazzling: Bristol blue scent bottles, delicate pink vases, creamy mini-sculptures of swans, sparkling Victorian decanters and shiny navy panels showing classical scenes.

In the early evening I go to the angular, teetering and downright peculiar Crooked House pub. This is on the edge of Dudley and makes you feel drunk without drinking because the building has a slope that drops 4ft from one side to the other: I feel as though I’m falling into the bar when I enter.

The slope is caused by subsidence from an old coal mine on the south side of the building. I drink a pint of mild, marvelling at the strangeness of it all and how coal still makes its mark in the Black Country (without actually turning it black these days).

NEED TO KNOW

Bed down at … The modern Copthorne Hotel Merry Hill (01384 482882, www.millenniumhotels.co.uk) on Brierley Hill, Dudley, overlooks a canal, has comfortable rooms and a pleasant restaurant and bar. B&B doubles from £90.

Chow down at … Black Country Living Museum (0121-557 9643, www.bclm.co.uk) has excellent fish and chips at £5. Entrance to the museum costs £12.95, or £6.95 for children aged 5-18. The Crooked House (01384 238583, www.thecrooked-house.co.uk) has an à la carte restaurant at the back. Two courses from £11.

What to see Broadfield House Glass Museum (01384 812745, www.dudley.gov.uk/ museums) on Compton Drive is worth a visit — as is the New Art Gallery Walsall (01922 637575, www.thenewartgallerywalsall.org.uk), a short drive away. Free entrance to both.

First published in The Times, July 25 2009

Great British weekend: Falkirk, Scotland

It looks like a row of giant bottle openers or perhaps a half-built Tube line in the sky. The Falkirk Wheel could pass for a superb piece of abstract sculpture.

On hearing that Falkirk, once renowned for its iron foundries, had a big wheel, I assumed that it was a version of the London Eye. But I was told that far from being a conventional big wheel, it was “the world’s only rotating boat lift”. I drove down the M9 from Edinburgh unsure what to expect.

Once there, I was led with others on to a boat in a canal at the base of one of the giant bottle-openers. Sitting on blue plastic seats, we were addressed by a jolly, ruddy-faced man named Roddy.

“We are now in a 300-tonne gondola,” he said. “We are about to go up there.” He pointed to another gondola. “That is 35 metres above us. Using the principle of Archimedes, we will soon be there, but we will use only the amount of electricity required to boil eight kettles.”

Lo and behold, perched in a gondola containing 500,000 litres (110,000 gallons)of water, the boat began to swing into the sky, climbing to the level of the Union Canal and leaving the Forth & Clyde Canal way below.

This is what makes the wheel, which opened in 2002 at a cost of £17.5 million, so useful: it connects these old waterways, opening up a new network of boating opportunities.

Afterwards I went to Falkirk’s Unesco World Heritage Site. A short drive from the wheel, passing a scrap-metal yard, I found myself at a section of the Antonine Wall, built by the Romans between AD142 and AD160, which runs 60km (40 miles) from the Forth to the Clyde.

I was the only tourist visiting the grassy mounds, which stretch like an enormous submerged snake for several hundred metres from a small car park to Rough Castle, a Roman fort.

The ancient turf wall marked the boundary of the Roman Empire, but is now broken and lost in many places amid modern developments.

Standing on the ramparts of the fort, there is a palpable sense of history: this is where civilisation once ended and the barbarians began. It is the most northerly of three walls built by the Romans — Hadrian’s Wall, begun in AD122, receives greater attention because it is a more prominent structure.