Category: Articles

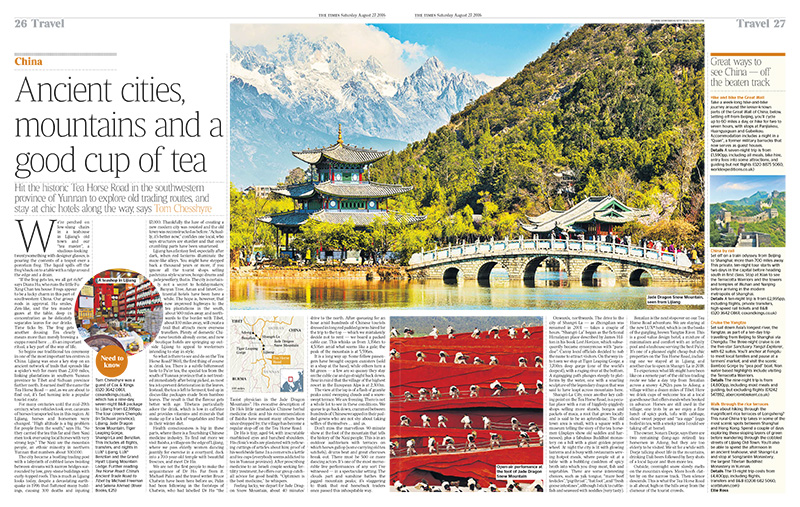

Guesthouses in paradise – Maldives on the cheap

Tuna fishing boat at dawn in Addu Atoll

THERE’S a party atmosphere on the roof of the ferry from Kulhudhuffushi to Malé. The sun is beginning to set in a blaze of orange and pink, and locals are sprawled on the roof gossiping, sharing jokes and sipping fizzy energy drinks. I am the only tourist on board for an overnight journey of roughly 200 miles, a southwards route that costs about £30 (or 15 pence a mile). For this princely sum I have a space on A-deck, a comfortable patch of green foam matting beneath softly whirring fans. On the roof of the ferry , though, there’s a natural breeze as we gaze out at the dramatic sky.

The locals about me, mainly resort workers, are returning on annual leave to their families in Malé, the bustling capital of this precariously watery nation of 1,200 islands (about 80 per cent of the land is at 1m above sea level, making it one of the most at-risk countries in the world from the rising sea). “Flying is too expensive,” says Ahmed, a dive instructor. “Anyway, going by boat is more fun.”

He’s right, and he’s also on to something that might well transform the way we go on holiday to the Maldives. In 2009 something quietly changed in this tropical Indian Ocean country. Before then it was illegal for tourists to travel “off-piste” to islands that were not official holiday resorts (of which there are about 100). The reason for this was that officials were fearful that westerners might spoil the Islamic way of life on the 300 or so islands inhabited by locals. However, a new government decided to open up these local communities so more people could benefit directly from tourist cash. And so, slowly, began the construction of a series of guesthouses on remote islands, some of which had not seen “outsiders” for years. In effect, without many foreigners realising that it had happened, a whole new country had opened up, away from the plush glossy magazine world of five-star resorts famous for their high service standards, spas and fancy water villas.

It was to this “new” nation that I spent almost two months travelling on ferries and cargo ships last year while researching my travel book Gatecrashing Paradise. The idea was to stay at the cosy new guesthouses (do not expect anything madly glitzy or flashy), and sometimes in spare rooms, to see the country from a different perspective, enjoying both the quiet and isolation of these islands and their natural beauty.

Ferries such as the one from Kulhudhuffushi to Malé took me from remote islands on Addu Atoll in the far south, beneath the Equator (where I joined a tuna fishing boat and watched the long joust-like rods pull in skipjacks at dawn), to the very north, 600 miles away. I travelled in a big figure of eight, downwards to Addu and then back up via little-visited, ancient Buddhist stupas (monuments) on Laamu Atoll, an island rebuilt after almost being washed away by the 2004 tsunami, and onwards to an artificial “emergency island” being constructed 2m above sea level (in case waters indeed rise as a result of climate change).

Utheemu, my most northerly stop-off, is where the great Maldivian hero Muhammad Thakurufaanu lived in the 16th century, leading a revolt against Portuguese raiders who had ruled the country for 15 years until 1573. Staying in a room at a local’s house (for £10 a night), I came to understand the immense pride Maldivians have in being independent for so many years; the period of British involvement in the islands from 1887 to the 1960s was as a “protected state”, with internal affairs run entirely without interference.

From Utheemu I visited the island of Makunudhoo, which is so remote that it does not feature in most guidebooks and is where some locals told me they had not seen a foreigner for more than 20 years. I was lucky to arrive on a festival day, enjoying a great feast of barbecued fish during a happy street jamboree lit by lanterns at a dusty crossroads. The beaches on Makunudhoo were deserted and probably the most picturesque I have ever laid eyes on, the waters alive with a kaleidoscope of glittering fish.

It felt at times as though I had come across a new, Indian Ocean version of Greek island hopping as it was when it first took off in the mid-20th century. I could hardly believe so many “undiscovered” little islands existed.

I became immersed in the country’s sometimes tricky politics, gossip and intrigue. I fell in love with its rich culture and fabulous food. Yes, the ferries were sometimes difficult — timetables were unreliable and word of mouth was usually the best way of knowing when to turn up at the docks — but there is, as I soon found, no better way of seeing this remarkable archipelago.

The American humourist PJ O’Rourke once quipped that “there are a lot of mysterious things about boats, such as why anyone would get on one voluntarily”. But that’s not true in the Maldives. Just hop on a ferry and see where it takes you.

Gatecrashing Paradise: Misadventures in the Real Maldives by Tom Chesshyre is published by Nicholas Brealey (£10.99). To order for £9.89 including free postage visit thetimes.co.uk/bookshop or call The Times Bookshop on 0845 2712134

Or see Amazon

Need to know

Trailfinders (020 73681200, trailfinders.com) has return flights from London to the Maldives from £596.

Great little places to stay in the Maldives

The garden at Reveries, Laamu Atoll

Reveries Diving Village, Gan, Laamu Atoll

There are 25 rooms at this popular guesthouse that includes the former Maldivian president Mohamed Nasheed among its guests. It’s right by a sandy beach and was one of the first guesthouses to open after the change in rules allowed foreign holidaymakers on “inhabited” islands. The peaceful tropical garden has a swing seat, perfect for lazing with a novel. Rooms are smart and very comfortable, with air-conditioning. There’s a central plunge pool next to a restaurant serving excellent fresh tuna dishes. Diving lessons are available on request. The website guesthouses-in-maldives.net is a good starting point for planning an island-hopping trip.

Details: Doubles are from about £110 with all meals and daily trips to a desert island where swimming in a bikini is allowed (guesthouses-in-maldives.net)

Asseyri Inn, Hanimaadhoo, Haa Dhaalu Atoll

Run by a young, laid-back couple, Asseyri has great-value rooms and can also arrange scuba diving as well as boat visits to a series of nearby islands including Utheemu, where guests can see the home of the 16th-century national hero Muhammad Thakurufaanu. The guesthouse is close to a beach and comes with one of the best restaurants serving Maldivian dishes such as garudiya, a clear tuna broth. The rooms are decorated with palm fronds and bright art. The owners can arrange packages with all meals and activities included, as well as internal flights to and from Malé, for those not wanting to take the ferry.

Details: B&B doubles are from about £70 (asseyri.travel/inn)

Ripple Beach Inn, Hulhumalé, Malé Atoll

Hulhumalé is connected to the island where most flights from abroad land (at Ibrahim Nasir International Airport) and Ripple Beach makes a good first-night stopover for those planning an island-hopping break. The rooms are compact but high-tech, with digital TV, air-conditioning and wi-fi. They also have charming hand-made furniture and polished coconut wood floors. The restaurant serves great tuna curries and sandwiches, overlooking a sandy beach with calm waters. There are nearby Maldivian restarants serving tasty “short eats” such as chilli salt prawns and cheese puffs (see maldivescook.com/snacks).

Details: Doubles are from about £26 (ripplebeachinn.com)

The SeaHouse Hotel Top Deck, Villingili, Malé Atoll

Another great choice for a first night, the SeaHouse Hotel had a different name (and was referred to as a guest house) when I visited. It’s on the little island of Villingili, close to a stunning beach that’s particularly good for swimming. The 31 rooms are spotless and modern. The island has more character than Hulhumalé and it’s commonplace to see locals playing football at sunset or chilling out on jolies, rudimentary chairs with a string-net seat. The hotel has a good brasserie and it is run by the same people behind the SeaHouse Cafe on Malé itself, a much-loved local institution renowned for its curries. There’s a good Chinese restaurant close to the SeaHouse Hotel.

Details: Doubles are from about £40 if booked through booking.com (www.seahousemaldives.com/topdeck)

Skai Lodge, Malé, Malé Atoll

This small B&B is tucked down a tiny lane not far from the artificial beach in the capital. It’s nothing fancy — the rooms are quite basic — but if you are after a feel of the bustle of Malé it’s a good, cheap base. Breakfast is served in a small room where Bollywood films are usually playing on the television. As well as being near the artificial beach it’s also close to the Maldivian parliament. Those after an alcoholic drink can catch a 15-minute ferry across to the airport island, where the Hulhule Island Hotel has a bar overlooking the sea.

Details: Doubles are from about £35 (skailodge.com.mv)

Arena Lodge Maldives, Maafushi, South Malé Atoll

The suites at this little guest house are colourful and clean, decorated in traditional Maldivian style. There are 12 altogether, each with air-conditioning. It’s an hour and a half south from Malé by ferry; the owners can provide details of timetables. They can also organise barbecues on deserted islands and watersports or snorkelling. There’s a lovely white-sand beach close by.

Details: Full-board rooms are from about £108 (guesthouses-in-maldives.net)

Happy Life Maldives, Dhiffushi, North Malé Atoll

It’s just 20m to the beach at the Happy Life . This four-bedroom lodge is bright and airy, with one of the rooms having a great sea view. All meals are included and the owners can advise on the best ferries to catch from Malé to arrive at Dhiffushi (the 2.30pm ferry from the capital should arrive at 5pm). Watersports and excursions can be organised; the use of a kayak is included.

Details: A night’s full board is from about £125 (guesthouses-in-maldives.net)

Charming Holiday Lodge, Hulhumeedhoo, Addu Atoll

Way down on the southern tip of the Maldives, Hulhumeedhoo is a ferry hop from the mainland of the atoll, which is linked by a nine-mile road (the longest in the country). This is an isolated place with a laid-back feel and the oldest cemetery in the Maldives, which is not far from the wonderfully named Charming Holiday Lodge. Rooms are contemporary in design with flatscreen televisions with satellite channels and air-conditioning. The owners can arrange fishing, snorkelling and cycling. They can also organise trips to the Herathera Island Resort & Spa to use its pools and bar.

Details: B&B doubles are from about £55 (charmingholidaylodge.com)

Equator Village Hotel, Gan, Addu Atoll

OK, strictly speaking this is not one of the new breed of guesthouses, but it makes a great spot for a couple of days on an island-hopping break. It’s in the old RAF barracks (the RAF had a base on Gan until 1976) with a laid-back feel and a fantastic pool with a licensed bar next to it. Gan counts as a “tourist resort” island, although it’s really best known for its airport and is quite unlike any of the other resorts. You can walk across a causeway from the island of Feydhoo, which is where ferries and cargo ships come in (I caught the overnight Naza Express cargo ship to Feydhoo from Malé).

Details: B&B doubles are from about £125 (equatorvillage.com)

Azoush Tourist Guest House, Fulhadhoo Island, Baa Atoll

With a population of just 300, Fulhadhoo is a tiny, peaceful spot. It’s about 2km long and less than a kilometre wide, and it holds a historical claim to fame as it is where the seaman Francois Pyrard de Laval was shipwrecked in 1602 (his account of his time in the islands is gripping and includes a description of the harrowing night when his ship hit the reef). Azoush has three comfortable, air-conditioned suites.

Details: Full-board doubles are from about £125 a night (guesthouses-in-maldives.net)

Ferry timetables: mtcc.com.mv, vermilliontransport.com, atolltransfer.com

Meeting the Salafists on Tahrir Square

‘Flock of crows: on holiday in Tahrir Square’ – by Tom Chesshyre

On my first day in Cairo during my journey across North Africa a year after the uprisings for my travel book A Tourist in the Arab Spring, I stumbled upon the Salafists of Tahrir Square. Before embarking on my journey I had little idea what a ‘Salafist’ was, but I had come to learn that the term referred to hard-line, ultra-conservative Islamists who favour a strict, puritanical version of sharia law that shuns modernity and harks back to the days of the Prophet Muhammad (at least as they choose to interpret the days of the Prophet).

The most controversial Salafists talked of jihad, a religious war to advance Islam. Their beliefs about women deeply concerned liberal-minded Egyptians; for example, the requirement to wear face veils, and a proposed ban on bikinis (outside of hotels quarantined from Egyptians, where bikinis would be allowed to maintain the tourist industry) and high heels (outside of private homes). ‘A woman can only wear high heels for her husband but she is not to do so outside her house,’ one preacher had declared. Another had said that the mingling of opposite sexes in public places should be prohibited. The Salafists of Egypt were much influenced by the Wahhabis of Saudi Arabia, who held similar beliefs and had spread their ideas into Egypt, partly through converting Egyptians who went to work in the Gulf in the 1970s to escape poverty at home.

Anyway, so there I was, on my first day, mixing with the Salafists of Tahrir Square. They wore white gowns similar to the traditional gallabiya favoured by most Egyptian men, but shortened so you could see their socks and sandals. This was the preferred Salafist style. They had gathered to demonstrate against the official disqualification of a Salafist presidential candidate named Hazem Salah Abu Ismail on the grounds that his mother was American. This was a claim he denied, saying that she only had a Green Card to live in the United States and had not converted nationality.

Images of the moon-faced politician with his bushy grey beard were on posters and placards all over the square. A popcorn stallholder, siding with his customers (one sensed his allegiance would switch depending on the day’s debate in Tahrir Square), boasted a picture of the Salafist on his wooden cart.

Ismail was in favour of women wearing veils and being segregated from men in the workplace. He would also have liked the age of marriage to be reduced to puberty, as it was during the time of the Prophet Muhammad. Some of his supporters favoured the stoning to death of adulterers and for thieves to have their hands cut off.

It is not often that one gets to mingle with such folk on a ‘holiday’. I bought a packet of sunflower seeds and salted peanuts, and strolled about. The atmosphere was a mixture of political intrigue and village fete. Munching on my sunflower seeds I listened to voices rising angrily from a small stage. Then I noticed something.

To the right of the ramshackle stage I was shocked to come across a section of swaying black fabric under a white canopy. For a split second I was reminded of a flock of crows. There was something disconcerting about the strange black space. Then I realised what I was seeing. The area under the canopy was where the Salafist women had gathered. They almost all wore full-length black robes with black veils and slits for their eyes – known as niqabs. A few did not wear veils and merely had black headscarves. The latter seemed more elderly than the others, though it was difficult to determine ages given how well covered everyone was. The women were penned into the small area behind a barrier and this was clearly the spot given over to female Salafists.

I bought a glass of orange juice from another stallholder. An eerie effigy of a man hung from a lamp post close by. I asked the stallholder who he represented. ‘This man is doing everything against them… so they hang him,’ he replied. Unlike the Salafists, the orange juice salesman wore jeans and a checked shirt. He seemed possibly more liberal than the ultra-conservatives at the demonstration – there must have been 500 people gathered in all. I inquired as to what he thought of the women in their pen.

His answer surprised me. ‘Only for her husband,’ he said, approving of the arrangement. ‘Beautiful woman, fine body…’ He indicated the shape of women’s breasts. ‘…only for her husband.’

It was a far cry from the images of Tahrir Square I had remembered from the news reports at the time of the revolution in January and February 2011, when President Mubarak stepped down after 18 days of demonstrations. Tahrir Square then had been the epicentre of the revolt, a symbol of the protest to introduce democracy, liberal ideals and a fairer system of governance in Egypt. By the time I arrived in February 2012, the political sands seemed to have shifted and another force was rising.

Eventually, of course, the less extreme Muslim Brotherhood went on to win the first properly democratic election in Egypt, only for President Morsi to be ousted by the military on the grounds of constitutional power grabbing. This left the country, considered by many to be the centre of the Arab world, in a mess. And it remains so today. The Salafists, many of whom agreed to back President Morsi in the elections to ensure an Islamist-led leadership, and other fundamentalists have taken to the streets and there has been much bloodshed.

A year after the revolutions, travelling as a tourist for my book, I knew there was trouble ahead. I also knew its source. The Salafists and the extremists were going to cause a stink. While the overthrowing of a dictator who had ruled the country for almost 30 years had captured the imagination of the world – with democracy heading for the heart of Arabia, Facebook uprisings and moderates leading the way – the reality was far removed.

And the darker side of Islam, in my view at least, was clear to see. It was the extreme Islamist position towards women. The calls for the public segregation of the sexes. The demands for the covering up of women’s bodies. The proposed bikini ban. The suggestion that the age of marriage be lowered to the age of puberty.

Was this what the Arab Spring revolution in Egypt, and perhaps in Tunisia and Libya too, would eventually lead to? Half the population wrapped up in niqabs… flocks of crows by the side of the stage.

* A Tourist in the Arab Spring by Tom Chesshyre (Bradt, £9.99)

UK and Ireland Hotel Reviews

15/11/14 – Oddfellows, Chester

8/11/14 – Sail Lofts, St Ives, Cornwall

1/11/14 – Swain House, Watchet, Somerset

25/10/14 – The Brimstone Hotel, Cumbria

18/10/14 – Congham Hall, North Norfolk

11/10/14 – The Godolphin Arms, Marazion, Cornwall

4/10/14 – The Angel, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk

27/9/14 – Kings Head, Cirencester

20/9/14 – Glazebrook House, South Brent, Deon

13/9/14 – The White Lion, Tenterden, Kent

6/9/14 – 2 Blackburne Terrace, Liverpool

30/8/14 – The Lord Crewe Arms, Blanchland, Co Durham

23/8/14 – The Church House, Midhurst, West Sussex

16/8/14 – Ham Yard Hotel, London W1

9/8/14 – The Close Hotel, Tetbury, Gloucestershire

2/8/14 – No 38 The Park, Cheltenham

26/7/14 – Nira Caledonia, Edinburgh

19/7/14 – The Crown, Amersham, Buckinghamshire

12/7/14 – Rowhill Grange Hotel, Wllmington, Kent

5/7/14 – Zanzibar International Hotel, Hastings, East Sussex

28/6/14 – The Archangel, Frome, Somerset

21/6/14 – Aston Hall, near Sheffield

14/6/14 – The Bull & Hide, London

7/6/14 – Driftwood Hotel, South Cornwall

31/5/14 – The Corran, Carmarthenshire

24/5/14 – The Red Lion, Babcary, Somerset

17/5/14 – The Old Rectory, North Devon

10/5/14 – The Bell Inn, Horndon-on-the-Hill, Essex

3/5/14 – Halcyon Apartments, Bath

26/4/14 – The Pier, Harwich, Essex

19/4/14 – Hotel du Vin, St Andrews

12/4/14 – The Cary Arms, Babbacombe, Devon

5/4/14 – Cromlix House (Andy’s Place), Kinbuck, Perthshire

29/3/14 – The Victoria, Holkham, North Norfolk

22/3/14 – The Chester Residence, Edinburgh

15/3/14 – The Pig, near Bath

8/3/14 – The Fuzzy Duck, Armscote, Warwickshire

1/3/14 – The White Horse, Chilgrove, West Sussex

22/2/14 – Great John Street, Manchester

15/2/14 – Malmaison Dundee

8/2/14 – Grays B&B, Bath

1/2/14 – Hard Days Night Hotel, Liverpool

25/1/14 – Ace Hotel, London E1

18/1/14 – The Light ApartHotel, Manchester

11/1/14 – Sands Hotel, Margate, Kent

4/1/14 – 131 The Promenade, Cheltenham

21/12/13 – The Tide House, St Ives, Cornwall

14/12/13 – The Porch House, Stow-on-the-Wold

7/12/13 – Dakota, Queensferry, Scotland

30/11/13 – Lewinnick House, Pentire, Cornwall

23/11/13 – Trevose Harbour House, St Ives, Cornwall

16/11/13 – At the Chapel, Bruton, Somerset

9/11/13 – Brook Green Hotel, London W6

2/11/13 – Bailbrook House Hotel, Bath

26/10/14 – The Inn at John O’Groats, Caithness, Scotland

19/10/13 – St Moritz Hotel, Trebetherick, Cornwall

12/10/13 – Linden House, Stansted, Essex

5/10/13 – Salcombe Harbour Hotel, Devon

28/9/13 – The Wild Rabbit, Kingham, Oxfordshire

21/9/13 – Isle of Eriska Hotel, Argyll, Scotland

14/9/13 – The Idle Rocks, St Mawes, Cornwall

7/11/13 – Dormy House, Broadway, Worcestershire

31/8/14 – The Wood Norton, Evesham, Worcestershire

24/8/13 – The White Hart, Somerton, Somerset

17/8/13 – The Cliff House Hotel, Ardmore, Co Waterford

10/8/13 – Laura Ashley The Manor, Elstree, Hertfordshire

3/8/13 – Stobo Castle, Peeblesshire

20/7/14 – No 11 Brunswick Steet, Edinburgh

13/7/13 – The Queensberry Hotel, Bath

6/7/13 – Great Northern Hotel, London

29/6/13 – Monachyll Mhor, Perthshire

22/6/13 – Cottage Lodge, Brockenhurst, Hampshire

15/6/13 – Greywalls, Gullane, East Lothian

8/6/13 – Danesfield House, Marlow-on-Thames

1/6/13 – The Angel & Blue Pig, Lymington, Hampshire

25/5/13 – The Swan, Lavenham, Suffolk

18/5/13 – Poets House, Ely, Cambridgeshire

11/5/13 – Cannizaro House, Wimbledon

4/5/13 – Escape B&B, Llandudno

20/4/13 – ME London

13/4/13 – The Greyhound on the Test, Stockbridge, Hampshire

6/4/13 – Roomzzz, Newcastle

30/3/13 – Eckington Manor, Worcestershire

16/3/13 – Thornbury Castle, Gloucestershire

2/3/13 – The William Cecil, Stamford, Lincolnshire

9/2/13 – The Kingham Plough, Oxfordshire

12/1/13 – The Lion Inn, Winchcombe, Gloucestershire

Chic hotels and modern art in the heart of Africa

An aardvark painted on the side of a home in the village of Kubuneh (more pictures at the end of the article)

Walking into Kubuneh we quickly realise that this is no typical West African tribal village. From the base of a giant kapok tree, an eerie face peers out, painted white on the bark. Its twisting, elongated visage (reminiscent of Edvard Munch’s The Scream) has a single eye and two crooked rows of clattering teeth.

Farther along, on the side of a hut with a corrugated roof, a multicoloured heron is daubed, its wings trailing extravagant streaks of black, white and grey. A path leads to another simple dwelling decorated with an electric blue lion’s head connected to a man’s body covered in tattoos. From the creature’s mouth billows a “roar” of scarlet paint covering an entire wall. Beyond is the spray-painted figure of an African boy holding a boom-box radio, with a hyena curled by his feet. On the same building, a naked woman is depicted, hunched over as she sets light to a clump of weeds.

It’s as though we’ve stepped into an avant-garde modern art gallery, yet we’re not so many miles from the run of mass-market hotels on the coast that have for years sullied the reputation of The Gambia’s tourism. We’re “up river” — eastwards down the River Gambia, along which this sliver of a country is based. We’re on the edge of a creek by Makasutu forest. This is a “sacred forest” (in the local Mandinka language), filled with mangroves, palms, mahogany, baobab and magnificent kepok trees.

The paintings are the result of Wide Open Walls, a street art project begun by Lawrence Williams, a fortysomething art school and film graduate from Kingston-upon-Thames. He came to The Gambia two decades ago and became involved at the Mandina River Lodge, an eco-hotel that’s about 20 minutes on a pirogue (boat) from Kubuneh. In the past few years Williams has quietly gone about encouraging Gambian artists to paint works in four villages in this remote spot. “It’s all about having fun and creating something magical,” he had told me the night before.

Williams himself has taken on the appearance of a work of art, so covered is he in tattoos, and wearing large circular tribal earrings. We spend a marvellous couple of hours wandering about the red-dirt tracks between single-story homes decorated with anteaters so big they look like dinosaurs, and giraffes with madly curving necks. A lizard with a flickering tongue is depicted clambering up the wall of a café. A tall, thin man is shown with a baby strapped to his back (usually it’s the women who carry youngsters in Gambian villages). He’s holding a sign that says “Baby on board”. A woman with an agonised face is painted on a nearby wall clasping her hands as though praying. Many of the works are by Njogu Touray,known by some as “West Africa’s Banksy”.

Tourism in the Gambia is moving on, with the village paintings just one of a series of projects hoteliers hope will make people think twice about the image of the “Costa del Sol of West Africa”, with its sordid edge of sex tourism involving both male and female visitors. At the Mandina River Lodge, which is decorated throughout with flair by Williams, a 20m tower has been constructed in a new area with a swimming pool by the creek. The top offers brilliant views across mangroves towards the river— a perspective that was previously impossible to see anywhere in the country.

I’m staying at an isolated lodge with stained glass windows that cast yellow, green and blue light on a giant four-poster bed with a huge mosquito net. As well as the striking street art, the highlight of my visit is a “sun-downer” boat ride, departing one afternoon at 4.30pm. I’m expecting a dawdle along the creek and a Julbrew beer (brewed in the capital, Banjul) as the sun drops away. Instead, we are treated to an explosion of birdlife as ospreys soar above, blue-chested bee-eaters flicker past, and cumbersome-looking goliath herons flap out of the mangrove with wing-tips just above the water. We also spot shiny black cormorants, pink-backed pelicans and African darters. The latter are curious creatures with long, thin, S-shaped necks that seem to dance forwards as they paddle in the olive-green water; for this reason they’re also dubbed “snake birds”.

The best is yet to come. Down a tributary creek we arrive at a series of trees covered in brown blobs. On closer inspection these turn out to be black kites, and soon they are taking to the royal blue sky, circling madly as if the scavengers are about to come for us (it’s all a bit Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds). Then we arrive at a small island where egrets are coming home to roost for the evening. Trees are almost entirely covered in white. At least a thousand birds squawk and screech — including many squadrons that turn up as we watch. All five of us on the tiny motorboat are for a while speechless; transfixed by the “show”.

Well-organised birdwatching tours are another way that officials hope to reposition the country’s tourism. While the politics of The Gambia have been fraught — the nation recently abruptly left the Commonwealth and President Yahya Jammeh has been accused of being increasingly autocratic (no local I talked to dared go on the record about him) — the reality is that holidaymakers are crucial to the livelihoods of many. Each job in tourism is said to provide for between 10 and 15 dependents.

I visit the Sandele Eco Retreat in the village of Kartong, close to the southern border with Senegal on the Atlantic Ocean. Solar panels provide electricity and clever ventilation systems are used in the four main lodges and the 20-room annexe. These work well: no need for air-conditioning. Instead of using wooden beams, ceilings are made of a lime “concrete” of ground oyster shells collected from the roots of mangroves.

Local craftsmen make the pretty jewellery sold in the shop; one has earned enough from sales to build his own house. The British owners Geri Mitchell and Maurice Phillips — who used to work in social services in the UK — intend eventually to pass on the resort to the local community. There are a lot of Brits in The Gambia, which was a British colony until independence in 1965. Mitchell told me that they aim to complete six further lodges. Each is plush, with big double beds, dome-shaped roofs and plunge pools — as well as ten more rooms in the annexe. They first opened with a couple of rooms in 2008, and have become a magnet for tour operators offering yoga breaks.

Sandele is just one of several new hotels that have opened over the past few years (see panel). As well as the glamorous Coco Ocean, which has a first-class spa and a whitewashed, minimalist Miami South Beach style, there’s the hippest new arrival: Leo’s Beach Hotel. This is on a quiet stretch of the coast, on a cliff, with great views across the Atlantic. It’s a handful of miles from the town of Senegambia, epicentre of the liveliest and some of the shabbiest tourism, where prostitutes and bumsters (hustlers) are commonplace.

Leo’s consists of five smart bedrooms and a large suite. The Austrian owners Nina Waitz and Alois Weiss fell for The Gambia during a holiday in 2009 and gave up jobs in publishing in Vienna to create an angular Bauhaus-style hideaway set around landscaped gardens with baobab and mango trees. They too have installed solar panels that work so well they are contributing electricity to the local grid. “It is nice to be self-sufficient,” says Waitz over coffee in their laid-back bar.

I go on a day-trip along the River Gambia to Jufureh, to see where Alex Haley, the American author of Roots, traced his ancestry back to the slave Kunta Kinte. It’s a gorgeous sunny day that begins in Banjul, close to the grand archway celebrating President Jammeh’s rise to power; no traffic is allowed to pass under the arch, and the rumours are that this is because its foundations are too weak. We chug along the river, passing the rugged tropical outline of Dog Island, before coming to a weather-beaten jetty. This leads to a statue of a figure holding his hands aloft clutching broken chains. A sign says: “Never again.”

Then we take in the Slavery Museum, which tells the story of tens of thousands of Senegambians (those from Senegal and Gambia) who were transported to the United States to work on plantations; many died because of the terrible conditions on the slave trade ships. Farther on, we meet the chief and make donations to the village. A guide tells me that he has met the civil rights leaders Louis Farrakhan of the Nation of Islam and Jesse Jackson, as well as Jermaine Jackson of the Jackson Five. Tourist cash, he says, now keeps the village going.

Among the holidaymakers on the boat back to Banjul — after seeing the slave fort on James Island — I talk to Monica Gordon from Cheam. Her mother emigrated to the UK from Jamaica in the 1950s. “Black history is not taught at all in schools in Britain. My kids have been taught nothing,” she says. “That’s why I’m here.”

Yes, the Gambia still has its tacky spots. Yet there’s a feeling of regeneration going on and plenty of reasons to go: boutique hotels, spas, Banksy-style art projects, stylish eco-resorts with yoga pavilions, world-class birdwatching tours. Don’t let the bumsters put you off.

Need to Know

Getting there

Tom Chesshyre was a guest of The Gambia Experience (0845 3302087, gambia.co.uk), which has a ten-night break with three nights staying at Ngala Lodge (B&B), Mandina River Lodge (half-board) and Coco Ocean (B&B) from £1,549pp, flights and transfers included.

Reading The Gambia (Rough Guide, £12 on Amazon). Water Music by T. C. Boyle (Granta, £7.99) is a fictionalised version of Mungo Park’s journey to discover the Niger River in the 18th/early 19th centuries.

Where to eat

The Calypso beach bar (00220 9920201) on Cape Point is a laid-back restaurant/bar selling tiger prawns with rice (about £12); it overlooks a crocodile pool and the outline of Senegal can be seen in the distance. The Rainbow Beach Bar (rainbow.gm) in Sanyang in the south has a backpacker feel, and offers chicken wraps and fish curries for about £5; Julbrew beers are about £1. The Gaya Art Café (gaya-artcafe.com), close to Senegambia but removed from the main strip of nightclubs, has a selection of tapas including coconut-covered prawns with soy sauce, hoummos and calamari, plus seafood salads and steaks; three courses about £15.

Further information

The Gambia Tourist Board (visitthegambia.gm). The main season is from September to April, although tourist officials are keen to point out that during the rainy season (May to October) rains usually last for only an hour at a time and quickly clear away. Visitors should take antimalarial medication. Flights from London take six hours and there is no time difference.

Where to stay

Ngala Lodge (www.ngalalodge.nl) is an 18-room boutique with a main building and two wings, completed in 2008. Modern and African art are mixed and there is a pool on a secluded terrace. The hotel is on a red-rock cliff with steps down to a wooden deck on a private beach. The restaurant serves excellent tiger prawns, seared tuna, salads and dorado chicken (in a peanut sauce). B&B doubles are from £150.

Leo’s Beach Hotel (leos.gm) is great value with B&B doubles from £91. It opened in January 2013. All the rooms have private balconies and the interior design would not look out of place in the pages of Wallpaper* magazine. There’s a lounge with a Mungo Park theme.

The Sheraton (sheratongambiahotel.com) is the best for families, with a massive central pool and a children’s pool, a long way from all the hustlers on the main street of Senegambia. It opened in 2007 and has 181 rooms; it’s the only international brand hotel in the country. There’s table tennis, a mini basketball court for children, a spa and a beach bar. B&B doubles are from £96.

The Kairaba (kairabahotel.com) can be found in Senegambia, but it is self-contained and it’s possible to stay without experiencing the bustle in the centre of the resort. The grounds are pretty, with sweeping lawns, and there’s a big main pool, with loungers. Rooms are comfortable and B&B doubles are from £115.

Mandina River Lodge (mandinalodges.com) is about an hour’s drive from the coast along a tarmac road heading to the interior and then down bumpy dirt roads. There are nine lodges, each well separated from the other for privacy; three are floating lodges on the creek. The centrepoint is a snaking pool next to three thatched open-sided buildings where food is served. Half-board doubles are from £220.

Coco Ocean Resort & Spa (cocoocean.com) is the slickest hotel and where visiting politicians usually stay. The main pool is on three levels on an elaborate central terrace leading to a private beach. There’s a good Thai restaurant and a swish spa (massages from about £30 an hour). B&B beach club doubles from about £260.

Sandele Eco Retreat (sandele.com) has the greenest credentials of all the country’s hotels, with the owners pursuing a carbon neutral policy. It’s far removed from the bustle of Senegambia and boat trips are organised to go on rivers close to Senegal. Rooms in the “lodge”, with its plunge pools, are from £80 per person per night, while those in the guest rooms are from £60 per person per night.

First published in The Times, December 21 2013

More street art in Kubuneh

The “Gambia dog” in Kubuneh

More street art in Kubuneh…

On a creek close to Mandina River Lodge